The soybean aphid was discovered in Wisconsin and the upper Midwest in 2000. Its current North American range includes 21 states and three Canadian provinces.

Soybean aphids cause damage by sucking plant sap. Soybean aphid outbreaks are associated with a reduction in plant height, pod number, seed size and quality, and yield. Symptoms of feeding damage may include plant stunting, and/or leaves covered with honey dew (the sticky substance excreted by aphids) and black sooty mold, a fungal growth on honey dew-coated leaves.

Soybean aphids are also capable of transmitting soybean viruses such as soybean mosaic virus and alfalfa mosaic virus. We do not recommend spraying insecticide to control virus infection, however, because it is not effective. Aphids present at spraying are killed, but can transmit virus before they die. The field is quickly recolonized by winged aphids and virus transmission can resume. Planting virus-free seed is the best way to prevent virus disease.

Life cycle and population growth

The soybean aphid has a complicated life cycle that is completed on two very different plant hosts. Aphids overwinter in the egg stage on the leaves of buckthorn. Two or three generations of wingless females are produced on the buckthorn in the spring, followed by a winged generation that leaves the buckthorn in search of soybean. In the summer, many generations of mostly wingless females are produced on soybean until decreasing daylength triggers production of winged adults and a return to buckthorn in the fall.

Scouting aphids

Start spot-checking seedling soybean and continue checking through pod fill. This aphid can be found on growing points and young leaves of early vegetative soybean plants. As soybean plants mature from late vegetative through reproductive stages, soybean aphids can be found on all plant parts. Although most common on undersides of leaves, they also occur on stems, petioles and upper leaf surfaces.

The insect is small (1/16 inch), pear-shaped bright green to yellow aphid with dark tips on the cornicles (two tube-like structures or “tailpipes” on the tip of the abdomen). Soybean aphids may be winged or wingless, or a combination of both on plants during the summer. Winged soybean aphids have a black head and thorax with green/yellow abdomen.

Higher populations of aphids are commonly observed on late-planted compared to early-planted soybean fields.

Aphids tend to build up more heavily on late-planted fields (see graph at right), so check late-planted fields closely. Moisture stress also favors aphid population growth and adds to yield risk.

Scout more intensively beginning at late vegetative growth stage soybeans and calculate average aphids per plant on 20-30 plants per field, from a sample covering at least 80% of the field area. Check the entire plant; at this stage aphids move from the top of the plant to the middle or lower areas of the canopy. Check the undersides of leaves, petioles and pods.

Take note of the presence of winged aphids and alatoid nymphs (with wing pads), high predator activity, and/or diseased aphids. These are all signs that the population may be in decline and/or may leave the field shortly. Scout these same fields again within a few days to note if populations are increasing or decreasing.

Aphid natural enemies

UW entomologists are studying natural enemies that occur in Wisconsin, and are also collaborating in a regional research project on importation biological control, also called classical biological control, of the soybean aphid. Importation biological control is a process which identifies, locates, evaluates, and releases a pest’s natural enemies that evolved with it in its native home. The goal is a significant reduction in aphid numbers. The Asian aphid parasitoid Binodoxys communis is the first candidate for classical biological control of the soybean aphid and has already been released in several midwestern states.

Economic threshold

The timing of an insecticide application is crucial. Use an action threshold of 250 aphids per plant. This action threshold should be based on an average of aphids per plant over 20-30 plants sampled throughout the field. Regular field visits are required to determine if aphid populations are increasing.

In replicated research trials, this threshold has worked well in R1 to R5 soybeans. Spraying at R6 or beyond has not been documented to increase yield. Look at Soybean Development Stages and Soybean Aphid Thresholds (a pdf file) for good photo close-ups of these critical growth stages.

This threshold incorporates an approximate 7-day lead-time between scouting and treatment to make spray arrangements or handle weather delays.

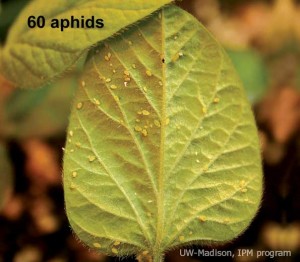

The UW Nutrient and Pest Management program published a Visual Guide to the Number of Soybean Aphids per Leaflet. Each soybean leaflet has a specific number of aphids displayed to help you count

Insecticide application to fields with soybean aphid populations below the economic threshold of 250 aphids/plant is not advised. The economic threshold (ET) of 250 aphids/plant is set below the Economic Injury Level (EIL), or “break-even” point where pest density causes yield losses equal to the cost of control.

For soybean prices within the $5.50-$6.50 range, the EIL, or number or aphids that need to be present for the value of lost yield to equal control cost, is approximately 674 aphids/plant. Under these crop prices, the Economic Threshold of 250 aphids/plant incorporates an approximate 7-day lead time between scouting and treatment to make spray arrangements or handle weather delays.

At higher market value for soybeans, a lowered EIL can be calculated based on damage relationships between soybean aphids and soybean yield over a wide range of densities, over three years across 6 states) (Journal of Economic Entomology 100: 1258-1276). For example, for soybeans at $15/bushel, with $8 control costs, and anticipated yield of 50 bu/acre, the EIL is lowered from 674 aphids/plant to 450 aphids/plant. The Economic Threshold of 250 aphids/plant is still below this revised EIL of ~450 aphids/plant, but decreases the lead time to 3-4 days to treat before reaching the EIL. The Economic Threshold of 250 aphids/plant has not changed.

In university research across the Upper Midwest, treating below 250 aphids/plant resulted in no detectable yield increase. 250 aphids/plant is not where economic injury begins, rather it is the action threshold at which to treat and prevent the field from reaching the EIL. In addition, early insecticide application will kill beneficial insects unnecessarily, allowing soybean aphid populations to rebound in a “natural enemy-free space”. Optimal treatment timing, and greatest economic return, result from treating soybean aphids at the Economic Threshold.

Plants are likely to be considerably above threshold if stems or pods are covered with aphids and honeydew, sooty mold covers the bottom leaves, and plants are stunted. Insecticide treatment is probably still of value, but the optimal time for treatment (greatest economic return) is past.

Insecticides

Consider the product choices for your situation. Pyrethroids (Warrior, Mustang Max, Asana, Baythroid) and organophosphates (Lorsban) are two insecticide classes labeled for soybean aphid on soybean and commonly used in chemical control programs. Organophosphates exhibit a ” fuming” action, which may work better in heavy canopies or at higher temperatures. Pyrethroids tend to provide longer residual than organophosphates or carbamates (Furadan) and are most effective at temperatures below 90°F.

Roundup Ready soybeans, soybean aphid, and the potential for soybean rust in Wisconsin have increased growers’ interest in combining all pesticide products into a single spray application. While convenient, these tank mixtures are not recommended. Insect, disease and weed pests do not all appear at the same time at economically damaging levels so a single tank mixed application will not provide satisfactory control of all three pest types. Additionally, sprayer specifications such as water volume, nozzle type (droplet size) and pressure must be optimized for each pest situation. For example, medium to fine droplet sizes suitable for many fungicide and insecticide applications are not appropriate for herbicide applications where larger droplet sizes are necessary to avoid herbicide drift.

For soybean aphid, good coverage is important. Higher spray volumes (15 to 20 gpa) and higher pressure help to move the insecticide down into the canopy.

Adding insecticide to early-season glyphosate applications as “insurance” is not recommended unless aphids are at threshold levels and actively increasing.