Damon L. Smith, Extension Field Crops Pathologist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Corn is looking pretty rugged in many areas of the Wisconsin corn belt. Areas in southern, southwestern, and south-central Wisconsin have experienced major foliar disease epidemics including the new disease, tar spot. Areas in eastern, east-central, and south-central Wisconsin have also seen heavy flooding and storm damage in corn fields. We have seen fields severely diseased, experiencing stalk rot, lodged, flooded – you name it, it has been a challenging finish to a season that had much promise.

How is tar spot affecting stalk integrity?

Figure 1. Stalks lodged due to reduced stalk integrity.

For corn foliar diseases such as northern corn leaf blight (NCLB) and gray leaf spot (GLS), it is well known that high severity can lead to stalk integrity issues. As foliage is damaged, less photosynthetic capacity is available from the leaves to produce carbohydrates for the plant. To fill an ear of corn, carbohydrates are needed from somewhere. In corn where the foliage is significantly damaged, the stalks become a considerable source to fill out the ear (a sink for nutrients). This leaves the stalk tissues devoid of carbohydrates leading to cell death and subsequent colonization of the stalk by fungal pathogens who are taking the opportunity to feed on a weak stalks. Thus, it isn’t uncommon to see stalk rots like Gibberella stalk rot, Fusarium stalk rot or Anthracnose stalk rot at higher incidence where high foliar disease pressure was observed (Fig.1). Where you find stalk rots, you often find root rots caused by the same pathogens. Root rot and stalk rot often go hand-in-hand.

Other causes for loss in stalk integrity can include large ears (nutrient sinks) that the plant can’t fill out, without using some of the stalk resources. In 2018 we saw many fields where the crop was moving through growth stages quickly and setting what appeared to be good yields. However, weather conditions changed midseason, with wet weather and more cloud cover, combined with nitrogen issues in some fields. This led to large ears that needed to be filled out, with again, limited photosynthetic capacity. The stalks were scavenged for carbohydrate, leaving them, again, with limited integrity.

Figure 2. An entire field lodged due to significant stalk rot

Now throw in some tar spot. Yet, another foliar disease that can limit photosynthetic capacity of the corn plant. We have observed many fields with significant stalk integrity issues. Whether just tar spot, or tar spot combined with GLS, NLCB, and/or stalk scavenging just for carbohydrates – stalks are in bad shape in many areas of Wisconsin. This is resulting in significant lodging issues in many fields, especially those hit with bad storms over the last several weeks (Fig. 2). Harvesting fields with low stalk integrity early will be key to protect yield potential. Conduct a “pinch” test or “push” test to determine which field have lower stalk integrity. Simply pinch stalks or push stalks to a 30 degree angle. Those plant that are soft and easily pinch or don’t pop back up after pushing, have stalk integrity issues. If 30-50% or more of these plants are identified with stalk integrity problems, they should be harvested first, to prevent yield losses from lodging.

What about tar spot, lodged corn, and mycotoxins?

Mycotoxins have not been implicated in the organisms reported to cause tar spot in Latin America. However, that doesn’t mean that other organisms that cause mycotoxins might not be present on harvested grain or silage. As plants dry down they can no longer actively fight fungal infection. We have looked at many brown and drying leaf samples from corn plants with tar spot. We do find many other fungal organisms, including Fusarium-organisms, which can produce mycotoxins. So while tar spot itself may not lead to mycotoxins, opportunistic fungi that colonize secondarily may result in elevated mycotoxin levels.

In addition, corn that has lodged and is in contact with the wet and saturated ground is at risk of being colonized by organisms that produce mycotoxins. Many of the known mycotoxin-producing fungi are found in the soil and on residue on the surface of the soil. If lodged corn is in contact with the ground and there is good moisture, it is possible that the ear and plant are being colonized and mycotoxins are being produced. So while your combine might be able to pick a plant up and harvest the ear, beware that it might be heavily colonized with organisms that produce mycotoxins. If taking corn for silage, lodged plants run the risk of significant hygiene issues in the bunker, including mycotoxins issues.

Where else can mycotoxins come from?

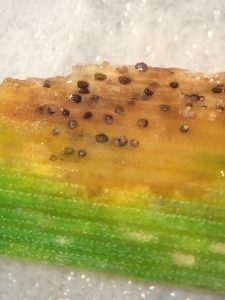

Figure 3. Diplodia ear rot on an ear of corn.

Corn ears don’t have to touch the ground to be infected with ear-rot fungi, they can also be colonized by ear-rot fungi through the silks. Given the kind of crazy year we have had, ear rot might be a significant concern in fields that saw erratic weather this season. Ear rots caused by fungi in the groups Diplodia (Fig. 3), Fusarium, and Gibberella will be the most likely candidates to watch for as you begin harvest. Fusarium and Giberrella are typically the most common fungi on corn ears in Wisconsin. This group of fungi not only damage kernels on ears, but can also produce mycotoxins. The toxins of main concern produced by these organisms are fumonisins and vomitoxin and can threaten livestock that are fed contaminated grain. Thus grain buyers actively test for mycotoxins in corn grain, and feed managers monitor silage for mycotoxin levels to be sure they are not above certain action levels established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The FDA has established maximum allowable levels of fumonisins in corn and corn products for human consumption ranging from 2-4 parts per million (ppm). For animal feed, maximum allowable fumonisin levels range from 5 ppm for horses to 100 ppm for poultry. Vomitoxin limits are 5 ppm for cattle and chickens and 1 ppm for human consumption.

For more information about ear rots and to download a helpful fact sheet produced by a consortium of U.S. corn pathologists, CLICK HERE.

How do I reduce mycotoxin risks at harvest?

Before harvest, farmers should check their fields to see if moldy corn is present. Sample at least 10-20 ears in five locations of your field. Pull the husks back on those ears and observe how much visible mold is present. If 30% or more of the ears show signs of Gibberella or Fusarium ear rot then testing of harvested grain is definitely advised. If several ears show 50-100% coverage of mold testing should also be done. Observe grain during harvest and occasionally inspect ears as you go. This will also help you determine if mycotoxin testing is needed.

If substantial portions of fields appear to be contaminated with mold, it does not mean that mycotoxins are present and vice versa. For example, Diplodia ear rot does not produce mycotoxins. However, if you are unsure, then appropriate grain samples should be collected and tested by a reputable lab. Work with your corn agronomist or local UW Extension agent to ensure proper samples are collected and to identify a reputable lab.

For more information on mycotoxins and to download a fact sheet, CLICK HERE.

Helpful information on grain sampling and testing for mycotoxins can be found by CLICKING HERE.

For a list of laboratories that can test corn grain for mycotoxins, consult Table 2-16 in UW Extension publication A3646 – Pest Management in Wisconsin Field Crops.

How should I store corn from fields with ear rots and mold?

If you observe mold in certain areas of the field during harvest, consider harvesting and storing that corn separately, as it can contaminate loads; the fungi causing the moldy appearance can grow on good corn during storage. Harvest corn in a timely manner, as letting corn stand late into fall promotes Fusarium and Gibberella ear rots. Avoid kernel damage during harvest, as cracks in kernels can promote fungal growth. Also, dry corn properly as grain moisture plays a large roll in whether corn ear rot fungi continue to grow and produce mycotoxins. For short term storage over the winter, drying grain to 15% moisture and keeping grain cool (less than 55F) will slow fungal growth. For longer term storage and storage in warmer months, grain should be dried to 13% moisture or less. Fast, high-heat drying is preferred over low-heat drying. Some fungi can continue to grow during slow, low-heat drying. Also, keep storage facilities clean. Finally, mycotoxins are extremely stable compounds: freezing, drying, heating, etc. do not degrade mycotoxins that have already accumulated in grain. While drying helps to stop fungal growth, any mycotoxins that have already accumulated prior to drying will remain in that grain. The addition of acids and reducing pH can reduce fungal growth but will not affect mycotoxins that have already accumulated in harvested grain.

For more information on properly storing grain and to download a fact sheet on the subject, CLICK HERE.

References

Munkvold, G.P. and White, D.G. Compendium of Corn Diseases, 4th Edition. APS Press.

In addition, This article is a compilation of the following previously written resources:

Smith, D.L. 2016. Wisconsin Late-Season Corn Disease Update. /2016/09/07/wisconsin-late-season-corn-disease-update/.

Smith, D.L. and Mitchell, P. D. 2016. Wet Wisconsin: Moldy Corn and Crop Insurance. http://ipcm.wisc.edu/blog/2016/09/wet-wisconsin-moldy-corn-and-crop-insurance/.