Wisconsin Soybean and Corn Disease Update – August 2, 2021

Damon Smith, Extension Field Crops Pathologist, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Brian Mueller, Assistant Field Researcher, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Camila Primieri Nicolli, Post-Doctoral Research Associate, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

It has been a while since I posted a corn and soybean disease update for Wisconsin in 2021, and that is because it has been reasonably quiet in the disease world up to this point. However, recent scouting and incoming reports indicate that this could change a bit as we move into August. Let’s take a look at what has happened so far this season and what to keep an eye out for over the next month or so.

The Soybean Situation

Figure 1. Phytophthora Root and stem rot of soybean

The Phytophthora Issue in Soybeans. During July we saw, and received reports, of some fields with Phytophthora root and stem rot of soybean (Fig. 1). I have received a lot of questions on why this happened. Are we seeing changes in the races of the Phytophthora organism in Wisconsin? My short answer is probably not. However, we have found a new species of Phytophthora in some fields that can affect soybean. The new species, Phytophthora sansomeana, can be found in mixed infections with P. sojae. Thus, even if we deployed the proper Rps resistances genes in our varieties, this “new” organisms might be causing some of the damage we observed this year.

We also are seeing fewer available soybean varieties with Rps 1K form of resistance. This form of resistance should be effective on about 99% of the fields in Wisconsin. Instead, we see varieties deployed that have the Rps 1c, Rps 1a, or no Rps gene indicated. Rps 1C is effective on about 75% of the acres in Wisconsin, just to give you some perspective. Thus, I don’t think this is necessarily an issue where we have seen race shifts in P. sojae, but a combination of issues where perhaps we aren’t deploying the correct resistance genes and we might have a new species of Phytophthora adding to the mix. You can learn more about managing Phytophthora root and stem rot of soybean in Wisconsin by clicking here. You will note that seed treatments can also be used to manage Phytophthora root and stem rot. You can click here to learn more about fungicide seed treatments and fungicide resistance in this group of organisms.

What’s Up with White Mold? For most of the state of Wisconsin, we are through the critical bloom time for infection by the white mold fungus. It is now really too late to make a fungicide application that is economically viable. However, scouting fields through August can help you determine what worked, what didn’t, and to figure out your harvest order. Remember, a great way to move the white mold fungus around is by contaminated combines at harvest. Start harvesting fields with no or low white mold incidence and work your way to those fields that look worse. Also consider cleaning combines between fields to limit movement of the fungal survival structures (a.k.a apothecia – the things that look like rat turds!) from one field to the next.

Look out for SDS. Now is also a good time to be scouting for sudden death syndrome (SDS) in soybeans. I’m not sure we will have a bunch of SDS this year in Wisconsin, but we will see pockets for sure. Knowing where you see it and what you did in 2021 can help with making variety and seed treatment decisions for 2022 and beyond. Remember that we do have decent partial resistance to SDS in many commercial varieties. Start here and choose the most resistant variety that fits your environment. Then consider layering a seed treatment (either Saltro or ILeVO) for improved management of SDS. You can learn more about seed treatment performance by studying the Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Soybean Seedling Diseases chart. You can also learn more about the performance of ILeVO in multi-state research trials by reading this report.

The Corn Situation

Corn in Wisconsin has been reasonably free of disease up to this point this season. However, we have noted a few foliar diseases beginning to pop up. We have observed gray leaf spot (GLS) becoming easy to find in most fields, while northern corn leaf blight (NCLB) is starting to show up in a handful of fields we have visited. We are also paying close attention to the tar spot and southern rust situations, I’ll expand on these below.

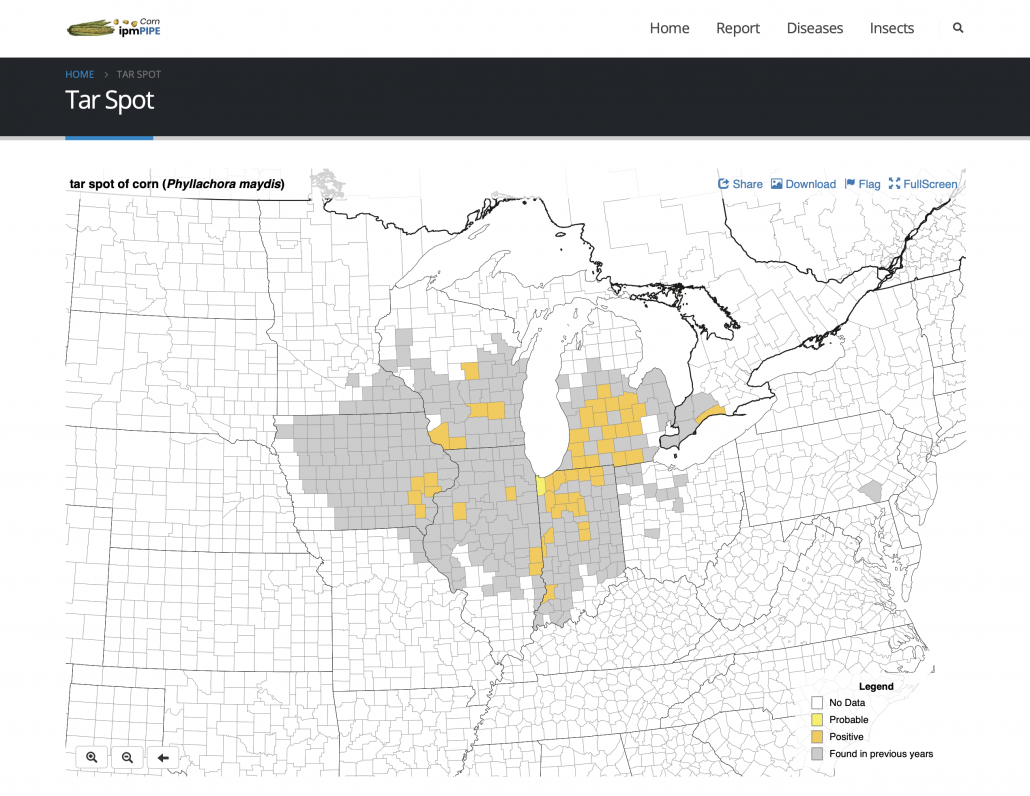

How bad is tar spot? The Tarspotter app has been running at moderate to high risk of tar spot increase over the last couple of weeks in Wisconsin. Our scouting has confirmed that tar spot is present in at least 5 counties so far in Wisconsin (Fig. 2). All but Grant County show tar spot to be easy to find, but it is present in the lower canopy at low severity. In Grant County, we had to hunt a long time to find 2 spots in a research field on a known susceptible. These observations align with Tarspotter as it indicated just moderate risk in the southwest quadrant of Wisconsin, with high risk from south central to the north. If you plan on spraying a fungicide to manage tar spot, we recommend that this be done soon, prior to the R3/R4 growth stage. The goal here is to protect the leaves from the ear leaf up from continued increase by the fungus. If you would like to learn more about tar spot check out the new web book published by the Crop Protection Network.

Figure 2. County-level confirmations of tar spot in the U.S. as of August 2, 2021.

Continue to scout for tar spot and let us know what you are finding. We are now accepting good pictures of tar spot to confirm its presence in counties where we have observed it in years past, in Wisconsin. In counites that tar spot has never been confirmed, we would like to get a physical sample to verify (Fig 2). Feel free to reach out to me if you do find tar spot or any other disease of corn or soybean for that matter.

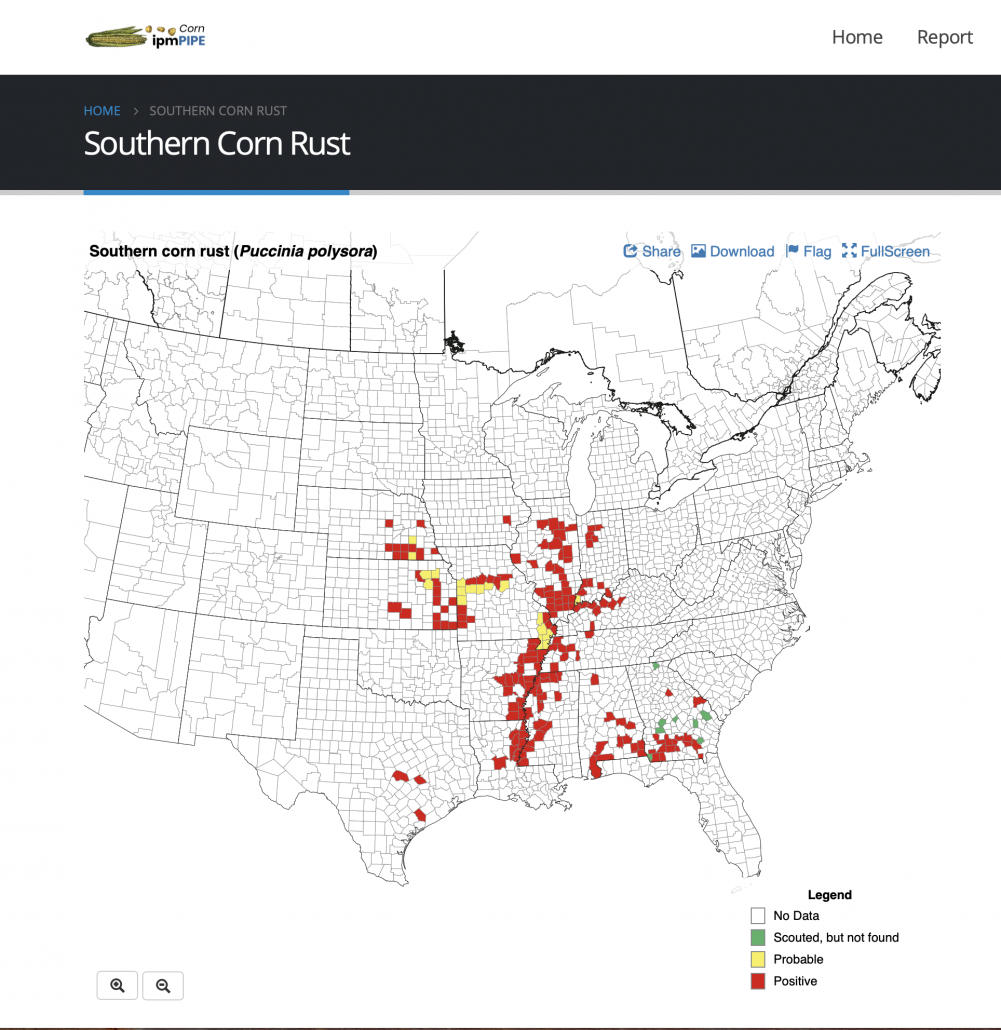

Figure 3. County-level confirmations of southern rust on corn in the U.S. as of August 2, 2021.

Has southern rust hit Wisconsin yet? The short answer is NO, not that we can find. We have scouted and asked several folks in our network, and nobody has observed and lab-confirmed southern rust in Wisconsin. However, figure 3 show county-level confirmations of southern rust of corn in the U.S. Based on this map, I would not be surprised if southern rust is confirmed in the next week or so in Wisconsin. Like tar spot, fungicides can be applied up to the R3/R4 growth stage with some benefits. Spraying after R4 will not yield economic returns. To learn more about managing southern rust of corn, check out the electronic fact sheet from the Crop Protection Network.

Keep an eye on the soybean and corn disease situation and scout, scout, scout. Let us know what you are finding!