Damon Smith, Extension Field Crops Pathologist, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Corn is approaching the V6-V10 range of growth stages in much of Wisconsin. With this, comes many questions about applying fungicide to control disease and preserve yield. What diseases are out there? What disease(s) should I focus on in-season? When should I spray? What should I spray? On top of these questions, we are also confronted with corn prices, which are notably optimistic this year, making folks think more about fungicide applications. So what should we consider for in-season disease management? Lets consider the diseases first, then the management decisions.

Figure 1. NCLB Lesions on a corn leaf

Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB): The most diagnostic symptom of NCLB is the long, slender, cigar-shaped, gray-green to tan lesions that develop on leaves (Fig. 1). Disease often begins on the lower leaves and works it way to the top leaves. This disease is favored by cool, wet, rainy weather. Higher levels of disease might be expected in fields with a previous history of NCLB and/or fields that have been in continuous and no-till corn production. The pathogen over-winters in corn residue, therefore, the more residue on the soil surface the higher the risk for NCLB. Management should focus on using resistant hybrids and residue management. In-season management is available in the form of several fungicides that are labeled for NCLB. However, these fungicides should be applied at the early onset of the disease and only if the epidemic is expected to get worse.

While I hate talking about threshold levels for managing disease, it can be helpful in your decision making process to know what might be severe. While scouting look in the lower portion of the canopy. If some symptoms are present in the lower canopy, make a visual estimation of how frequent (percentage of plants with lesions) NCLB is in a particular area and how severe (how much leaf area is covered by NCLB lesions. The lower leaves aren’t responsible for much yield accumulation in corn, but spores produced in NCLB lesions on these leaves can be splashed up to the ear leaves where disease can be very impactful. So by scouting the lower canopy and getting an idea of how much disease is present, you can “predict” what might happen later on the ear-leaves to make an informed spray decision.

Figure 2: A computer simulation of 5% NCLB severity on a corn leaf.

The other consideration you should make while scouting is the resistance rating that the hybrid has for NCLB. If it is rated as resistant, then NCLB severity might not be predicted to get very severe, while in a susceptible hybrid, NCLB might be present on 50% or more of plants at high severity levels. Note however, that even if a hybrid is rated as resistant, it can still get some disease. Resistance isn’t immunity! If NCLB is present on on at least half the plants and severity is at least 5-10% and weather is forecast to be rainy and cool, a fungicide application will likely be needed to manage the disease. So what does 5% leaf severity look like? Figure 2 is a computer generated image that shows 5% of the corn leaf with NCLB lesions. You can use this image to train your brain to visually estimate how severe the disease might be on a particular leaf. As for fungicide choice and timing, I consider that further below.

Figure 3. Gray Leaf Spot lesions on a corn leaf.

Gray Leaf Spot (GLS): Gray leaf spot typically starts as small blocky or jagged, light tan spots. These can expand to become long, narrow, rectangular lesions (Fig. 3) that may have yellow or orange halos around them. Gray leaf spot is typically worse when temperatures are warm and humidity is frequently above 90%. Thus, in Wisconsin, this disease is generally more frequent in the southern and southeastern portion of the state. Conditions that favor GLS often do not favor NCLB. The GLS pathogen and NCLB pathogen have different temperature requirements. Yield loss from GLS will be the greatest if lesions develop on the ear-leaves right before and right after tasseling. Like NCLB, hybrids rated as susceptible will generally suffer greater yield reductions due to gray leaf spot. Management of GLS should focus on choosing hybrids with excellent resistance and managing corn residue. Corn residue allows the pathogen to overwinter.

Like NCLB, fungicides can also be used to manage gray leaf spot. However, these should be applied as preventative applications. Thus, using the same rule of thumb to make a spray decision for GLS as for NCLB can help you make the decision to spray fungicide. As for fungicide choice and timing, I will also consider that further below.

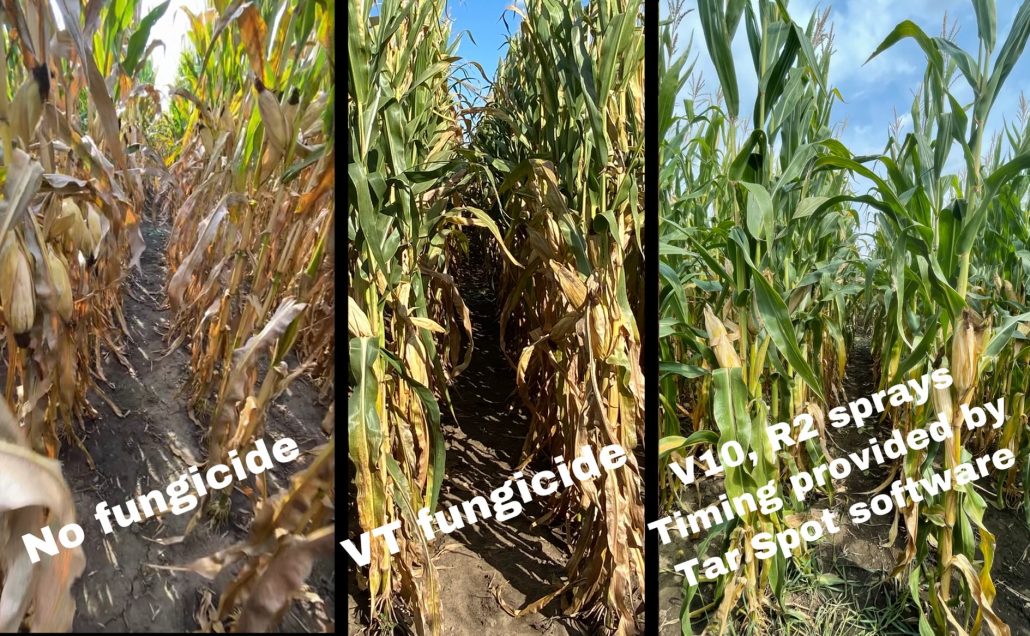

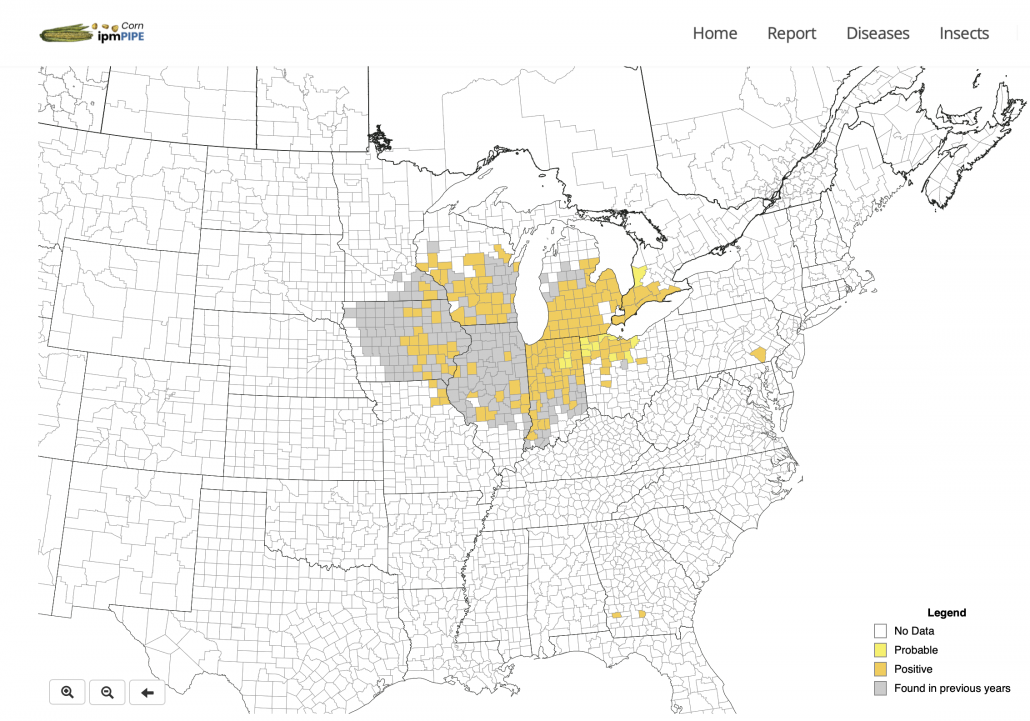

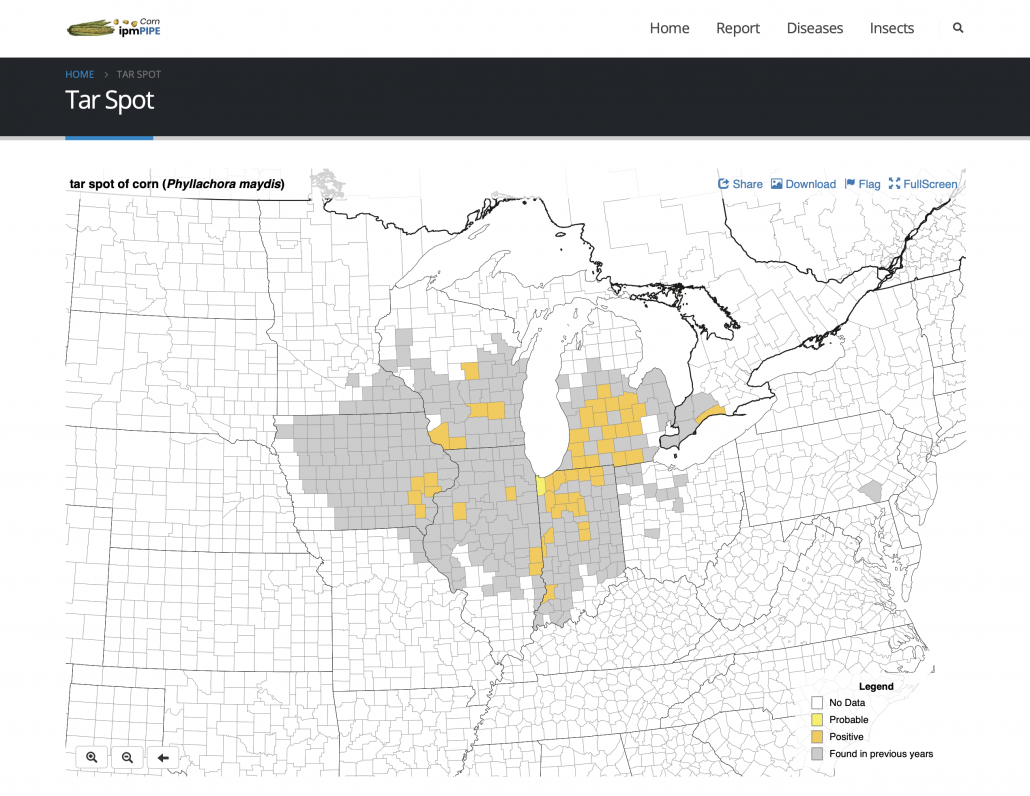

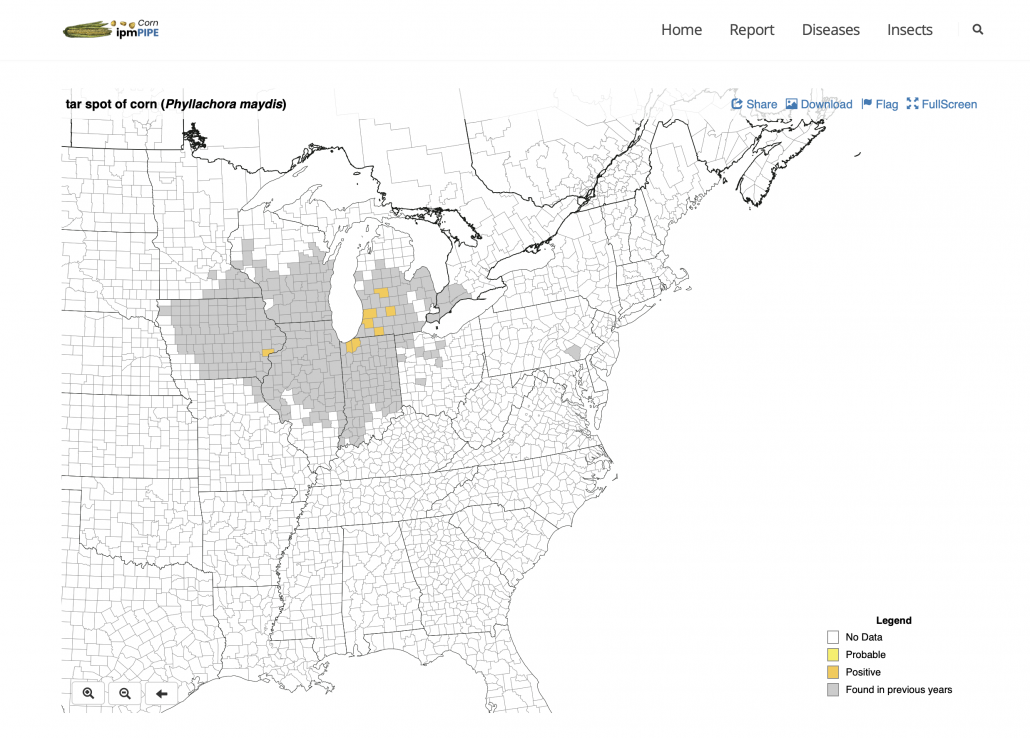

Figure 4. Tar Spot Signs and Symptoms on Corn Leaves

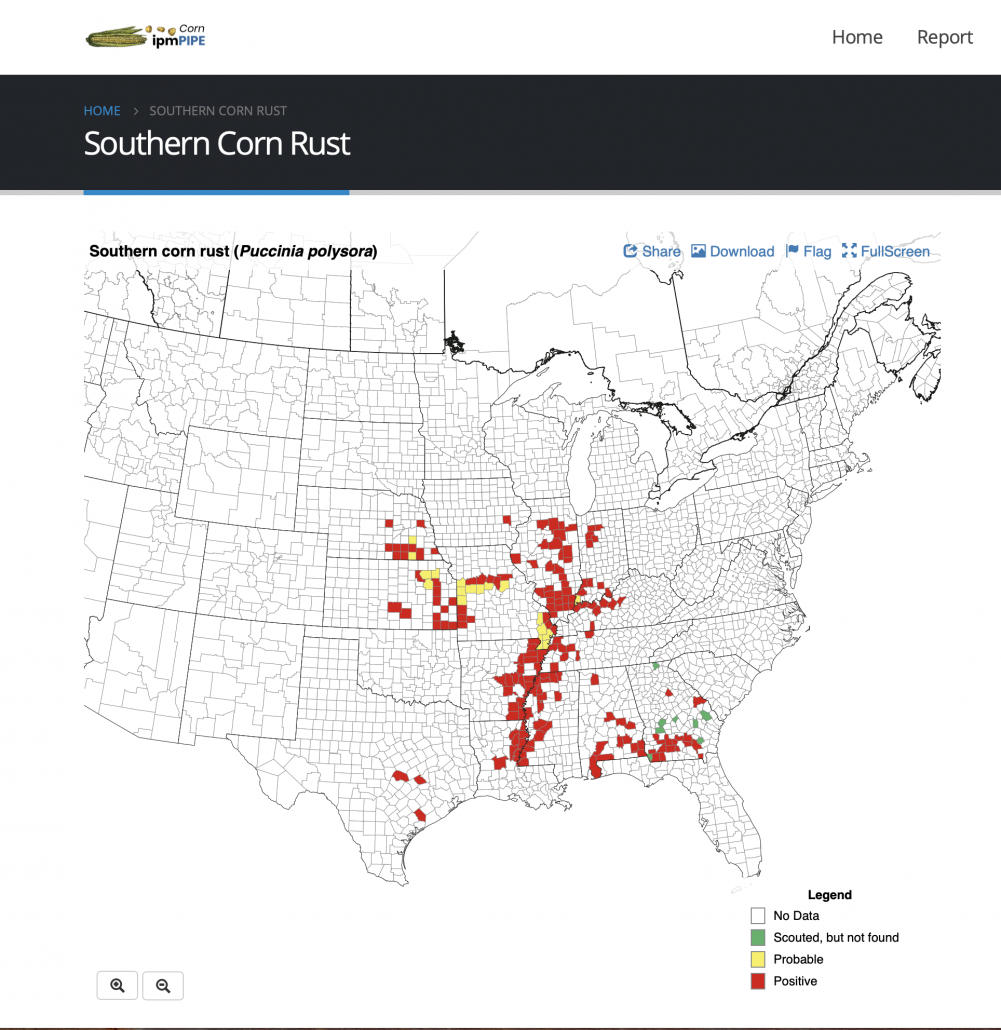

Tar Spot: Tar spot is favored by cool conditions (60-70 F) and high relative humidity (averages above 75%). Over the last several seasons the tar spot pathogen, Phyllachora maydis, has been able to cause yield reductions in parts of the Midwest by itself. There seems to be no need for a second fungus, Monographella maydis to be present to cause “fisheye” symptoms along with severe necrosis and early dry down. In addition, work done in the Midwest shows that the tar spot fungus can overwinter on corn residue from the previous season. So like with NCLB and GLS fields with high levels of infested residue might be more prone to infection by the tar spot fungus.

Not a lot is known about hybrid resistance to tar spot. Losses as high as 50-60 bushels per acre have been recorded on some hybrids, while others in the same field were only marginally affected. Partial resistance might be present in Midwest on certain corn hybrids. However work is ongoing to understand which hybrids those might be. Fungicide applications have been shown to reduce tar spot levels. However, timing of application must coincide with disease onset and product choice is important. Mixed-mode-of action fungicides have been the most consistent in efficacy over the past several seasons (more on that below). More information on tar spot can be found by in the Tar Spot Electronic Book.

Figure 5. Eyespot symptoms on a corn leaf.

Eyespot: Eyespot typically first develops as very small pen-tipped sized lesions that appear water-soaked. As the lesions mature they become larger (¼ inch in diameter) become tan in the center and have a yellow halo (Fig. 5). Lesions can be numerous and spread from the lower leaves to upper leaves. In severe cases, lesions may grow together and can cause defoliation and/or yield reduction. Eyespot is also favored by cool, wet, and frequently rainy conditions. No-till and continuous corn production systems can also increase the risk for eyespot, as the pathogen is borne on corn residue on the soil surface. Management should focus on the use of resistant hybrids and residue management. In-season management is available in the form of fungicides. Severity has to reach high levels (>50%) before this disease begins to impact yield. I often have eyespot present in my corn trials each year as we plant into continuous corn and use no-till. However, we typically do not see yield reductions from this disease even in non-sprayed plots. When scouting, note the disease and keep track of the severity. Again, fungicides should be applied early in the epidemic and may not be cost effective for this disease alone.

What Disease(s) Should I Focus on In-Season? Based on the information above, the greatest emphasis for Wisconsin should be placed on controlling NCLB, GLS, and tar spot (what I call the ‘Corn Foliar Disease Trifecta!). Most hybrids planted in Wisconsin will be resistant to eyespot.

What Should I Spray, and When Should I Spray for Corn Foliar Diseases In Wisconsin? Fungicide should be used to preserve yield and reduce disease level. There is no silver bullet fungicide out there for all corn diseases. However, there are many products which work well on a range of diseases. The Corn Fungicide Efficacy table lists products that have been rigorously evaluated in university research trials across the country. You can see there are several products listed that perform well on NCLB, GLS, and tar spot. So obviously, if a disease is present and you are trying to control the disease, you might expect more return on your investment, compared to simply spraying fungicide and hoping that there might be a yield increase.

Paul et al. (2011) conducted research to investigate the return on investment (ROI) of using fungicide at low and elevated levels of disease. Data from 14 states between 2002 and 2009 were used in the analysis. They looked at 4 formulations of fungicide products across all of these trials. I won’t go into detail about all products, but will focus on one here, pyraclostrobin. This is the active ingredient in Headline® Fungicide. In all, 172 trials were evaluated in the analysis and Paul et al. found that on average there was a 4.08 bu/acre increase in corn grain yield when pyraclostrobin was used. So there does appear to be some increase in yield with the use of fungicide over not treating across a range of environments.

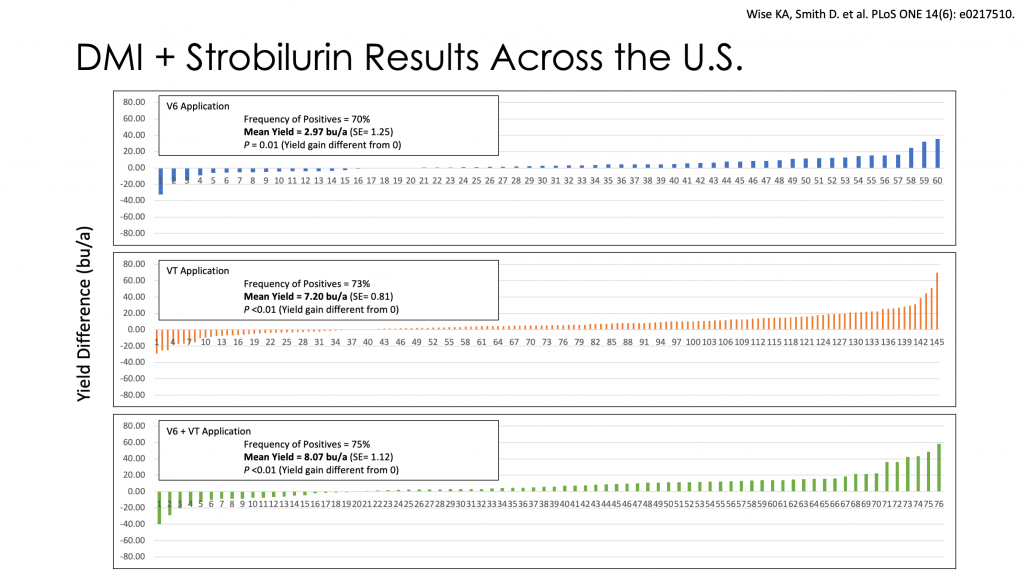

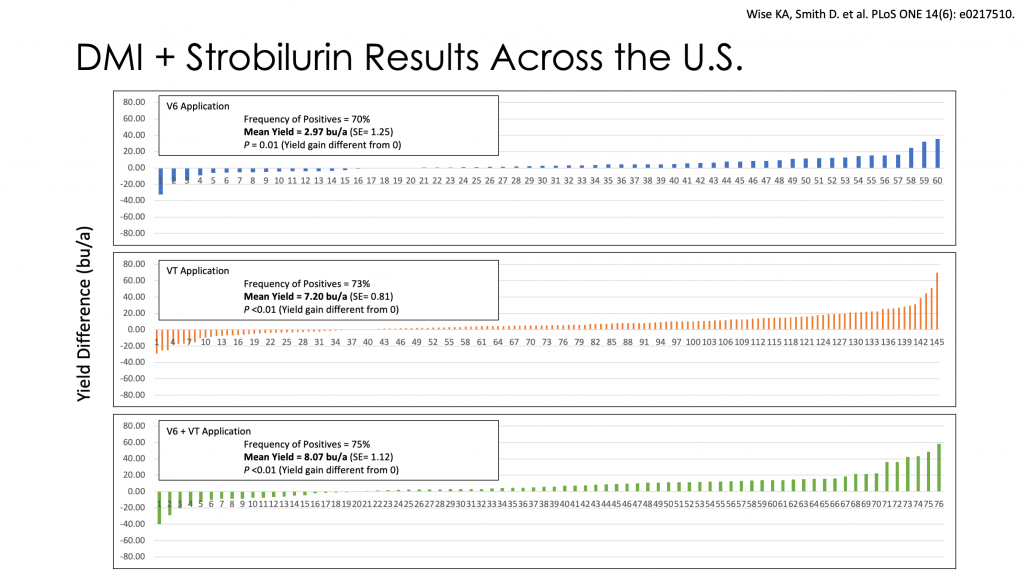

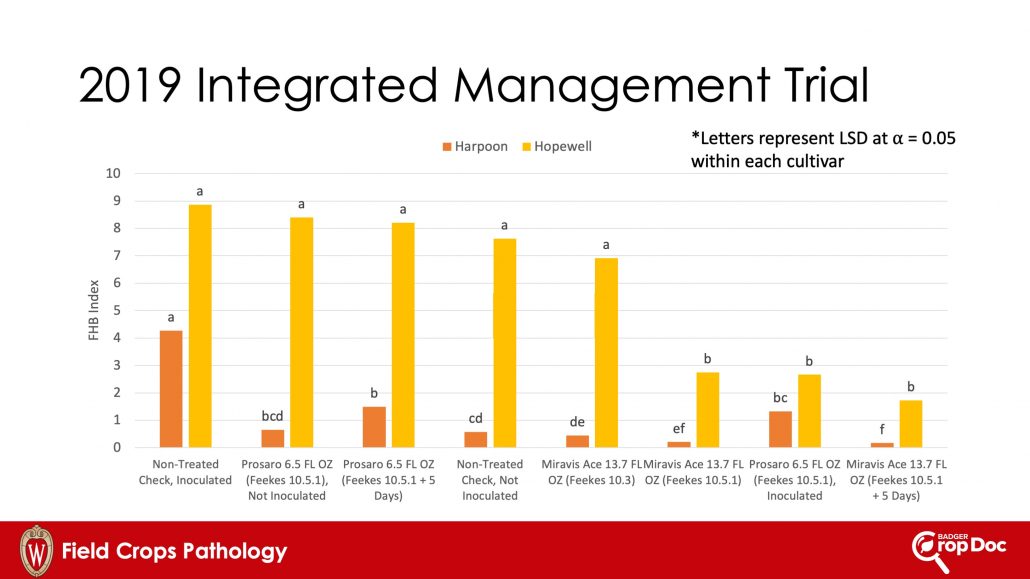

Figure 6. Average yield preservation of QoI+DMI fungicide applications over not-treating across the U.S. corn belt at the V6, Vt, and V6+VT application timing.

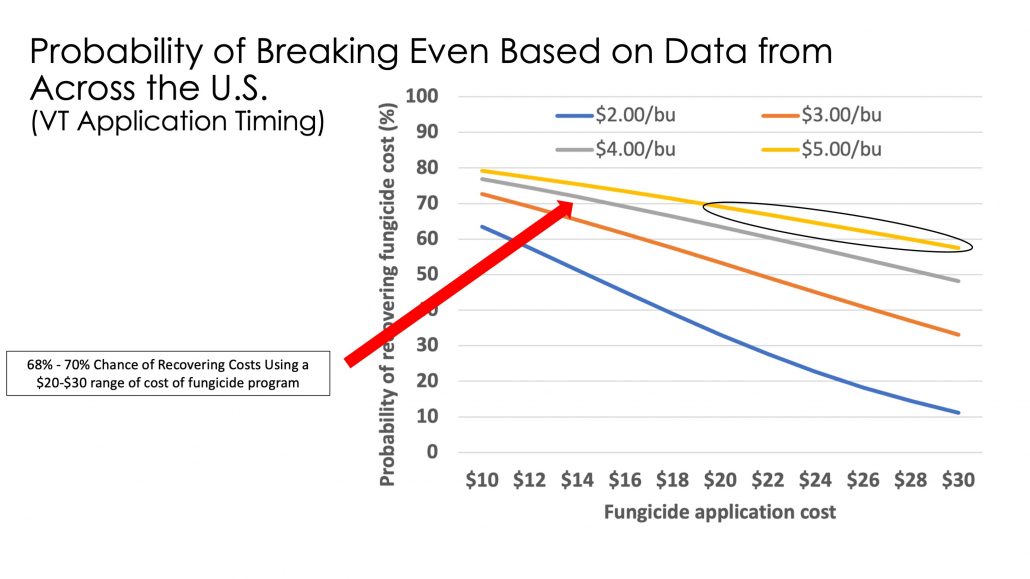

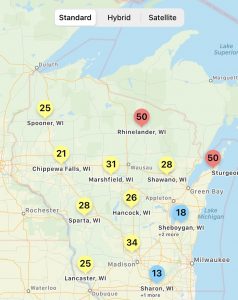

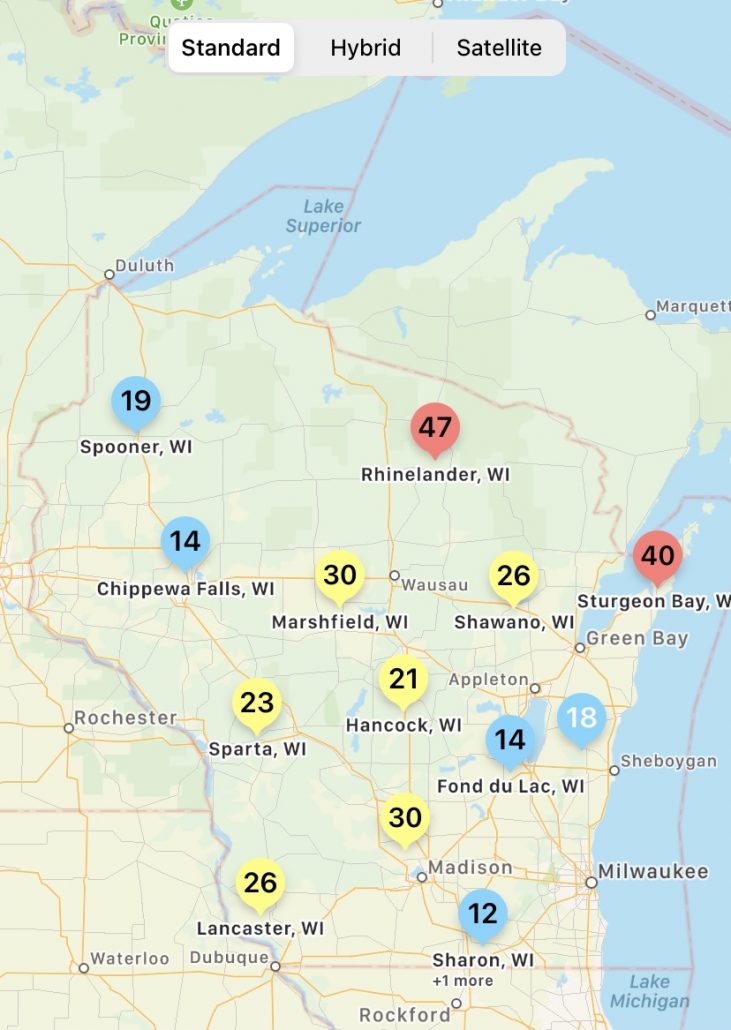

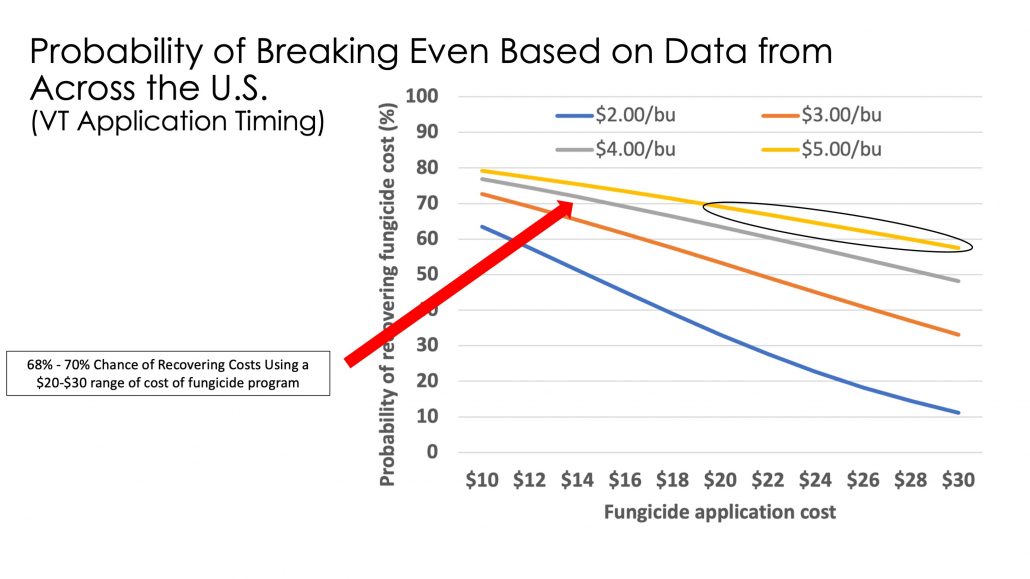

Let’s Take a Closer Look at Corn Fungicide Return on Investment (ROI): In our current market, what are the odds that we might break even on a fungicide application in 2021? Today’s corn future price for September has a bushel of corn above $5.00. While most of the early work on fungicide use in corn has focused on Headline® Fungicide, much of the industry has transitioned to using multi-mode-of-action products. These would be products mostly containing strobilurin (QoI), triazole (DMI), and/or succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor (SDHI) fungicides in the same jug. Details about fungicides and fungicide mode of action can be found on the Fungicides for Field Crops Information Page. Products such as Headline AMP® or Quilt Xcel® would fall into the QoI + DMI category. These combination products have also been fairly consistent in response in my fungicide trials. You can find summaries of these trial results here. If we consider using Quit Xcel® at 10.5 fl oz or Headline AMP® at 10.0 fl oz, the list pricing of the products plus adding aerial application costs, result in a range of cost of $20 – $30 per acre to make the applications at VT. If we can sell corn for at least $5.00 per bushel then we would need to preserve 4 bu/acre to 6 bu/a in yield over not treating to break even!

In a recent analysis of corn yield data where DMI+QOI products were applied at the tasseling period (VT) across the entire corn belt, the average yield preservation over not treating was 7.20 bu/a (Fig. 6). Thus, with the strong corn prices projected this fall, there could be some opportunity to come out ahead with a fungicide application, especially if forecasted rain events come to fruition and make disease issues increase. The projected probability of breaking even in the current economy with $5.00/bu corn is between 68% and 70% (Fig. 7). If we can sell our corn for a better price or make the applications cheaper, then the odds will continue to improve. We also know that in Wisconsin, the odds of breaking even improve further if NCLB or GLS are active and increasing during the tasseling period. Get out there and scout!

Figure 7. Probability of Breaking Even Based on Data from Across the U.S. (VT Application Timing)

So What About Fungicide Application Timing? We can investigate this question over the U.S. corn belt using the same dataset. Applications focused on an early (V6) timing, a VT-R2 timing, or a combination of V6 plus a VT-R2 application. Let’s again focus on the QoI+DMI products. Based on observations across the corn belt the V6 timing averaged almost 3 bu/a of preserved yield over not treating (Fig. 6). The VT application resulted in nearly 7.2 bu/a in preserved yield, while the two-pass program only offered a little over 8 bu/a. Clearly the higher average yield preservation occurs using a single application of fungicide at the VT-R2 timing. Wisconsin data has been consistent with this observation. Thus it is recommended that a single application of fungicide be used around the VT-R2 growth stages, when NCLB or GLS are active and increasing on or near the ear leaves.

What About Silage Corn and Ear Rot? When it comes to ear rot control and reducing the accumulation of mycotoxins in grain or silage corn, fungicide application should be made when white silks are out. Spores of fungicide that generally cause mycotoxin issues in the grain portion of corn will infect the plant through silks. Thus, apply fungicides during silking or within 5-10 days after silking starts, can be beneficial. Note that if the goal is to target mycotoxin production and reduce deoxynivalenol (DON) accumulation in the grain portion of the plant, products containing a DMI component should be used. Results where QoI + DMI products were used on silage corn can be found in our 2019 Fungicide Test Summary and again in our 2020 Fungicide Test Summary.

Finally, be aware that in some cases, application of fungicide in combination with nonionic surfactant (NIS) at growth stages between V8 and VT in hybrid field corn can result in a phenomenon known as arrested ear development. The damage is thought to be caused by the combination of NIS and fungicide and not by the fungicide alone. To learn more about this issue, you can CLICK HERE and download a fact sheet from Purdue Extension that covers the topic nicely. Considering that the best response out of a fungicide application seems to be between VT-R2, and the issues with fungicide plus NIS application between V8 and VT, I would suggest holding off for any fungicide applications until at least VT. If you want to spray earlier than VT, keep the NIS out of the tank!

Summary

As we approach the critical time to make decisions about in-season disease management on corn, it is important to consider all factors at play while trying to determine if a fungicide is right for your corn operation in 2021. Here is what you should consider:

1) Corn hybrid disease resistance score for NCLB and GLS (and perhaps tar spot too, if known) – Resistant hybrids may not have high levels of disease which impact yield.

2) Get out of the truck and SCOUT, SCOUT, SCOUT – Consider how much disease and the level of severity of disease present in the lower canopy prior to tassel.

3) Consider weather conditions prior to, and during, the VT-R2 growth stages – if weather is conducive for NCLB, GLS, and or tar spot then disease may continue to increase in corn and a fungicide application might be necessary. If it turns out to be hot and dry, disease development will stop and a fungicide application would not be needed.

4) Consider your costs to apply a fungicide and the price you can sell your corn grain – Will you preserve enough yield out of the fungicide application to cover its cost? The 2021 season is looking decent to break even on that investment, but this is not the norm.

5) Hold off with making your fungicide application in Wisconsin until corn has reached the VT-R2 growth stages – The best foliar disease control and highest likelihood of a positive ROI will occur when fungicide is applied during this timing when high levels of disease are likely.

6) Be aware that every time you use a fungicide you are likely selecting for corn pathogen populations that will become resistant to a future fungicide application – Make sure your fungicide application is worth this long-term risk. See fact sheet A3878 below for more information.

Other Resources

Impact of foliar fungicide timing and fungicide class on corn yield response in the United States and Ontario, Canada

Fact Sheet: A3878 – Fungicide Resistance Management in Corn, Soybeans, and Wheat in Wisconsin

VIDEO: Researching Fungicide Applications for Grain-Corn, Effect on Yield & Cost Recovery

References

Groves, C.L., Kleczewski, N.M., Telenko, D.E.P., Chilvers, M.I., and Smith, D.L. 2020. Phyllachora maydisascospore release and germination from overwintered corn residue. Plant Health Progress. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHP-10-19-0077-RS.

Munkvold, G.P. and White, D.G., editors. 2016. Compendium of Corn Diseases, Fourth Edition. APS Press.

Paul, P. A., Madden, L. V., Bradley, C. A., Robertson, A. E., Munkvold, G. P., Shaner, G., Wise, K. A., Malvick, D. K., Allen, T. W., Grybauskas, A., Vincelli, P., and Esker, P. 2011. Meta-analysis of yield response of hybrid field corn to foliar fungicides in the U.S. Corn Belt. Phytopathology 101:1122-1132.

Wise, K., Mueller, D., Sisson, A., Smith, D., Bradley, and Robertson, A., editors. 2016. A Farmer’s Guide to Corn Diseases. APS Press.

Wise, K.A. and Smith, D.L., Freije, A., Mueller, D.S., Kandel, Y., Allen, T., Bradley, C.A., Byamukama, E., Chilvers, M., Faske, T., Friskop, A., Hollier, C., Jackson-Ziems, Kelly, H., Kemerait, B., Price, P., Robertson, A., and Tenuta, A. 2019. Meta-analysis of yield response of foliar fungicide-treated hybrid corn in the United States and Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE 14(6): e0217510. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0217510.

Help the CPN determine how to serve you best through this short

Help the CPN determine how to serve you best through this short