Damon Smith, Extension Field Crops Pathologist, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Shawn Conley, Extension Soybean and Small Grains Agronomist, Department of Plant and Agroecosystem Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Rains continue to fall around Wisconsin. While we still have a moderate drought in much of the state, some of that drought is being alleviated. However, with these timely rains, come disease concerns. Here are our thoughts on what is happening.

Phytophthora Root and Stem Rot of Soybean

Figure 1. Stem rot symptoms of Phythophthora rot and stem rot on soybeans.

It has been a couple of years since we have seen a significant epidemic of Phytophthora root and stem rot (PRSR) of soybean. However, since it has started raining, we have got a good look at how susceptible many of our soybean varieties are here in Wisconsin. PRSR is primarily cause by the fungal-like organism, Phytophthora sojae. PRSR is usually worse in fields that are no-till and/or are slow to drain. The PRSR pathogen likes to survive in old soybean residue and can also persist as a long-term survival structure in the soil itself. The organisms that causes PRSR becomes active if the soil temperatures are over 60 F and the soil becomes saturated. We had those conditions occur back in early to mid-July. Once the soil dried out a bit and a bit of environmental stress kicked in, we can readily observe the damage the organism caused in early July. Primarily what we are seeing right now is the stem rot phase (Fig. 1), with the symptoms including wilting of the plant and a distinct purple-brown lesion extending from the soil surface upward. If plants are pulled from the ground, you will also see poor root systems which is where the organisms typically first infects and causes damage.

At this point in the season, there is nothing that can be done. DO NOT spray foliar fungicides for this problem. This will not be effective. You will want to check on the variety with the symptoms and consult the tech sheet to see what type of “Phytophthora gene” may have been included in the variety. These genes are called Rps genes and provide race-level resistance. The population of the PRSR pathogen can be a single race or mixed races in the field. The last time a survey of Phytophthora races was done in Wisconsin, it was noted that the Rps 1-k resistance gene should be effective on about 99% of the acres in the state. However, that survey was done over 15 years ago. Due to heavy use of the Rps 1-k resistance gene, we believe that the population in the state has shifted. We are seeing that resistance readily overcome. Unfortunately, most of the varieties currently grown in the state have this resistance. A recent check of the soybean variety trials 2022 show that out of 265 varieties tested 25% had no PRSR resistance gene, 2% had Rps 1-a, 29% Rps 1-c, 26% Rps 1-k, 9% Rps 3-a, and 9% had multi-genes. We are actively working with the Wisconsin Soybean Marketing Board to understand what the current population looks like. However, it is too early to tell what the races are primarily in our fields. Moving forward. perhaps choosing Rps 3-a or mixed gene varieties could help, but that is a shot in the dark for now.

Other things you can do for PRSR are to open up the rotation between soybean crops, and improve drainage in fields that are typically saturated for long periods of time. Like I said above, adjusting variety choice can help too. Seed treatment fungicides can also be used. However remember that the seed treatment is only going to be effective for the first 30 days or so after planting. After that we have to rely on varietal resistance to manage this problem. If you would like to find efficacy data on the seed treatments you can find that HERE.

We are looking for samples of PRSR from around Wisconsin. So feel free to reach out (damon.smith@wisc.edu) and we can coordinate getting samples sent to us. This will help with our survey efforts and eventual varietal recommendations.

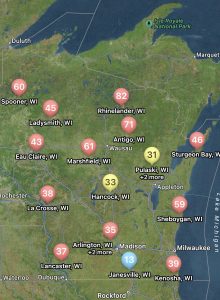

Tar Spot Update

Figure 2. A Screen shot of a map developed in the Field Prophet app showing risk for tar spot development in Wisconsin as of July 27, 2023.

You can find the most recent updates on tar spot confirmations across the U.S. here: https://corn.ipmpipe.org/tarspot/. Tarspotter is also showing mostly moderate to high risk across the state of Wisconsin (Fig. 2). This means you should be actively scouting for tar spot at this time. The risk is likely that you will find it across much of the state. If the corn growth stage is between VT/R1 and R3, then you might go ahead and consider a fungicide application. Our research has shown that one well-timed application of fungicide somewhere between VT/R1 – R3 will control tar spot enough for a yield response even in a heavy-pressure year. You can learn more about managing tar spot by clicking here. If you think you found tar spot I would appreciate if you would let us know. We can enter the county level data into the Corn IPMPipe Map and contribute to the cause.

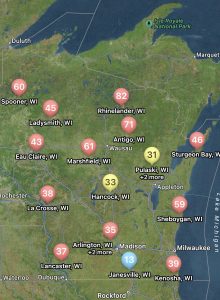

White Mold Update

Figure 3. Sporecaster predictions for selected non-irrigated locations in Wisconsin for July 27, 2023.

The risk for white mold according to Sporecaster is a bit more spotty, compared to tar spot. Mostly the northern tier of the state is at high risk while central and southern Wisconsin varies from moderate to low (Fig. 3). If you are in a low-risk area and you are at R3 or beyond, you might not have much to worry about for this year when it comes to white mold. However, if you are in a moderate-risk zone, watch this situation carefully. If you are at R3 and the crop has good canopy, you might consider one late R3 application. If you are in a high-risk zone, the crop has canopied, and your soybean crop is in the bloom period, it is time to think about a fungicide application. The recent rains have made the risk in these areas generally stay high or increase. These will be the areas I would expect to find white mold 1-3 weeks from now. If you would like to learn more about white mold management, check out my previous article HERE.

As always, get out and look the crop. Scout, scout, scout!