Corn Diseases of 2015 and Should I Spray Fungicide?

Damon L. Smith, Extension Field Crops Pathologist, University of Wisconsin

The phone has been ringing a lot lately and the primary questions are:

- What corn diseases should I be concerned with this year in Wisconsin?

- Should I spray a fungicide? And If so, what product and timing?

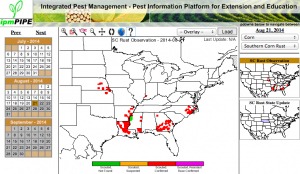

Lets start with the first question. As far as foliar disease issue, I think we need to scout closely for northern corn leaf blight (NCLB) in Wisconsin. The Midwest is already seeing high levels of this disease and it is showing up in the lower canopy in corn fields in southern Wisconsin. Remember, that this disease can be easily confused with Goss’s wilt. Earlier this season I wrote a post about differentiating these two diseases. I encourage you to revisit that post as a refresher. In addition to NCLB, our scouting has revealed a second foliar disease present in the lower and mid-canopy of the corn crop. That second disease is eyespot. Lets talk about NCLB and eyespot in a little greater detail.

Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB): The most diagnostic symptom of NCLB is the long, slender, cigar-shaped, gray-green to tan lesions that develop on leaves (Fig. 1). Disease often begins on the lower leaves and works it way to the top leaves. This disease is favored by cool, wet, rainy weather, which has seemed to dominate lately. Higher levels of disease might be expected in fields with a previous history of NCLB and/or fields that have been in continuous and no-till corn production. The pathogen over-winters in corn residue, therefore, the more residue on the soil surface the higher the risk for NCLB. Management should focus on using resistant hybrids and residue management. In-season management is available in the form of several fungicides that are labeled for NCLB. However, these fungicides should be applied at the early onset of the disease and only if the epidemic is expected to get worse.

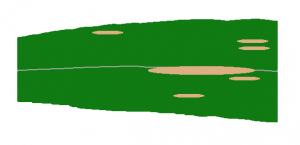

While I hate talking about threshold levels for managing disease, it can be helpful in your decision making process to know what might be severe. While scouting look in the lower portion of the canopy. If some symptoms are present in the lower canopy, make a visual estimation of how frequent (percentage of plants with lesions) NCLB is in a particular area and how severe (how much leaf area is covered by NCLB lesions. The lower leaves aren’t responsible for much yield accumulation in corn, but spores produced in NCLB lesions on these leaves can be splashed up to the ear leaves where disease can be very impactful. So by scouting the lower canopy and getting an idea of how much disease is present, you can “predict” what might happen later on the ear leaves to make an informed spray decision. The other consideration you should make while scouting is the resistance rating that the hybrid has for NCLB. If it is rated as resistant, then NCLB severity might not be predicted to get very severe, while in a susceptible hybrid, NCLB might be present on 50% or more of plants at high severity levels. Note however, that even if a hybrid is rated as resistant, it can still get some disease. Resistance isn’t immunity! If NCLB is present on on at least half the plants and severity is at least 5-10% and weather is forecast to be rainy and cool, a fungicide application will likely be needed to manage the disease. So what does 5% leaf severity look like? Figure 2 is a computer generated image that shows 5% of the corn leaf with NCLB lesions. You can use this image to train your brain to visually estimate how severe the disease might be on a particular leaf. As for fungicide choice and timing, I consider that further below.

Eyespot: Eyespot typically first develops as very small pen-tipped sized lesions that appear water-soaked. As the lesions mature they become larger (¼ inch in diameter) become tan in the center and have a yellow halo (Fig. 3). Lesions can be numerous and spread from the lower leaves to upper leaves. In severe cases, lesions may grow together and can cause defoliation and/or yield reduction. Eyespot is also favored by cool, wet, and frequently rainy conditions. No-till and continuous corn production systems can also increase the risk for eyespot, as the pathogen is borne on corn residue on the soil surface. Management should focus on the use of resistant hybrids and residue management. In-season management is available in the form of fungicides. Severity has to reach high levels (>50%) before this disease begins to impact yield. I often have eyespot present in my corn trials each year as we plant into continuous corn and use no-till. However, we typically do not see yield reductions from this disease even in non-sprayed plots. When scouting, note the disease and keep track of the severity. Again, fungicides should be applied early in the epidemic and may not be cost effective for this disease alone.

What fungicide should I spray and should I spray at all? My question is what are you trying to do? Control a disease or simply boost yield? Fungicide should be used as a tool to control a disease and preserve yield. There is no silver bullet fungicide out there for all corn diseases. However, there are many products which work well on a range of diseases. The Corn Fungicide Efficacy table lists products that have been rigorously evaluated in university research trials across the country. You can see there are several products listed that perform well on both NCLB and eyespot. So obviously, if a disease is present and you are trying to control the disease, you might expect more return on your investment, compared to simply spraying fungicide and hoping that there might be a yield increase.

Paul et al. (2011) conducted research to investigate the return on investment (ROI) of using fungicide at low and elevated levels of disease. Data from 14 states between 2002 and 2009 were used in the analysis. They looked at 4 formulations of fungicide products across all of these trials. I won’t go into detail about all products, but will focus on one here, pyraclostrobin. This is the active ingredient in Headline® Fungicide. In all, 172 trials were evaluated in the analysis and Paul et al. found that on average there was a 4.08 bu/acre increase in corn grain yield when pyraclostrobin was used. So there does appear to be some increase in yield with the use of fungicide, but in our current market, will this average gain cover the fungicide application?

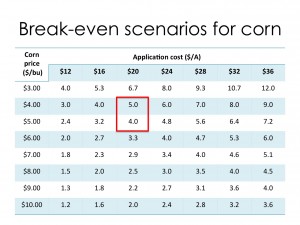

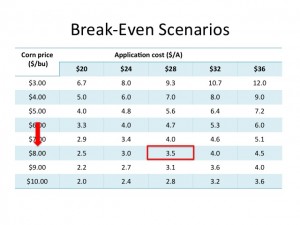

The suggested application rate for Headline® Fungicide is 6 to 12 fl oz/acre. My latest cost sheets indicate that at the 6 fl oz/acre rate, the cost of the product alone would be about $20/acre. Note that this does not include the custom applicator cost. This is a variable expense that would need to be added in to get an accurate ROI for your operation. Today we can estimate that we might sell corn grain somewhere between $4 and $5 per bushel. We can then use the cost of the fungicide product and the price of grain to figure out how many bushels of corn we need to make in the crop that would be treated with pyraclostrobin vs. non-treating. Figure 4 is a table with various corn prices along the vertical axis and fungicide costs per acre along the horizontal axis. The cells indicate the bushels of corn per acre needed to break even when using a fungicide at the corresponding cost and corn grain sale price. Using the above scenario, we see that with corn priced between $4 and $5 per acre and a fungicide application cost of $20/acre, we would need to gain 4-5 bushels per acre when using Headline® Fungicide in the current corn market. Obviously these calculations are for just one product, but you can do the same for your farm and fungicide program and use the table to figure out what break-even yield gain you will need to cover your costs.

What are the odds of getting that 4 to 5 bushel per acre yield gain when using Headline® Fungicide? Paul et al. went further and calculated the probability of return at various corn prices and fungicide costs. They did separate analyses for foliar disease severity less than 5% and greater than 5%. In our current corn market with around $4/bu corn prices and a cost of Headline® Fungicide at $20/acre, Paul et al. found that at low foliar disease levels (<5% severity) the odds of a positive ROI using the fungicide would be around 50%. The odds of a positive ROI improve if disease severity is greater than 5%. In their calculations with higher levels of disease (>5% severity), the odds of a positive ROI would be between 60% and 70%. The morale of this story is that if you are going to use fungicides on corn, they should be targeted toward fields that will have, or are at risk, for disease!

So what about fungicide application timing? Over the last several years corn pathologists in the U.S. corn belt have conducted fungicide application timing trials on corn for grain. Programs included various products, but applications focused on an early (V5-V8) timing, a VT-R2 timing, or a combination of V5-V8 plus a VT-R2 application. Over a 5 year period and nearly 1,500 observations, the average yield gain when using fungicide at V5-V8 alone was 1.4 bu/acre, while that at the VT-R2 timing was 4.4 bu/acre, and 4.7 bu/acre for the two pass program. In Wisconsin in 2013, the best gain in yield when using fungicide was at the VT application timing with almost 10 bu/acre over the non-treated. In 2014, we saw the opposite, with an average loss of grain yield at the VT timing of around 10 bu/acre. In Wisconsin, we see that yield gain in fungicide trials is highly variable and depends on the hybrid and weather for that particular season. You can check out results of the fungicide trials and the performance of various products over the last two years by visiting my Fungicide Test Summaries page and viewing the results in the 2013 and 2014 reports.

Finally, be aware that in some cases, application of fungicide in combination with nonionic surfactant (NIS) at growth stages between V8 and VT in hybrid field corn can result in a phenomenon known as arrested ear development. The damage is thought to be caused by the combination of NIS and fungicide and not by the fungicide alone. To learn more about this issue, you can CLICK HERE and download a fact sheet from Purdue Extension that covers the topic nicely. Considering that the best response out of a fungicide application seems to be between VT-R2, and the issues with fungicide plus NIS application between V8 and VT, I would suggest holding off for any fungicide applications until at least VT.

Summary

As we approach the critical time to make decisions about in-season disease management on corn, it is important to consider all factors at play while trying to determine if a fungicide is right for your corn operation in 2015. Here is what you should consider:

1) Corn hybrid disease resistance score – Resistant hybrids may not have high levels of disease which impact yield.

2) Get out of the truck and SCOUT, SCOUT, SCOUT – Consider how much disease and the level of severity of disease present in the lower canopy prior to tassel.

3) Consider weather conditions prior to, and during, the VT-R2 growth stages – if it is cool and wet, disease may continue to increase in corn and a fungicide application might be necessary. If it turns out to be hot and dry, disease development will stop and a fungicide application would not be recommended.

4) Consider your costs to apply a fungicide and the price you can sell your corn grain – Will you gain enough out of the fungicide application to cover its cost?

5) Hold off with making your fungicide application in Wisconsin until corn has reached the VT-R2 growth stages – The best foliar disease control and highest likelihood of a positive ROI will occur when fungicide is applied during this timing when high levels of disease are likely.

6) Be aware that every time you use a fungicide you are likely selecting for corn pathogen populations that will become resistant to a future fungicide application – Make sure your fungicide application is worth this long-term risk. To learn more about fungicide resistance, you can CLICK HERE to download a UW Extension fact sheet.

Other Resources

Wisconsin Field Crops Fungicide Information Page

Diseases Showing up in Iowa Corn, 2015

UNL CropWatch: Worn Disease Update

References

White, D.G., editor. 2010. Compendium of Corn Diseases. APS Press.

Paul, P. A., Madden, L. V., Bradley, C. A., Robertson, A. E., Munkvold, G. P., Shaner, G., Wise, K. A., Malvick, D. K., Allen, T. W., Grybauskas, A., Vincelli, P., and Esker, P. 2011. Meta-analysis of yield response of hybrid field corn to foliar fungicides in the U.S. Corn Belt. Phytopathology 101:1122-1132.