Tasseling Corn – Scout Now for Foliar Diseases and What About Fungicide?

Damon L. Smith, Extension Field Crops Pathologist, University of Wisconsin

I have been riding through much of the southern tier of Wisconsin this week and am noticing quite a few corn fields that are beginning to tassel. This growth stage presents itself as a good time to scout for foliar diseases of corn and make decisions on in-season management for any diseases you might find.

As for which diseases might be important this year? I wish I had a crystal ball. However, if I had to make an educated guess, three come to mind: Northern corn leaf blight, Eyespot, and Anthracnose leaf blight.

Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB): The most diagnostic symptom of NCLB is the long, slender, cigar-shaped, gray-green to tan lesions that develop on leaves (Fig. 1). Disease often begins on the lower leaves and works it way to the top leaves. This disease is favored by cool, wet, rainy weather, which has seemed to dominate lately. Higher levels of disease might be expected in fields with a previous history of NCLB and/or fields that have been in continuous and no-till corn production. The pathogen over-winters in corn residue, therefore, the more residue on the soil surface the higher the risk for NCLB. Management should focus on using resistant hybrids and residue management. In-season management is available in the form of several fungicides that are labeled for NCLB. However, these fungicides should be applied at the early onset of the disease and only if the epidemic is expected to get worse.

Eyespot: Eyespot typically first develops as very small pen-tipped sized lesions that appear water-soaked. As the lesions mature they become larger (¼ inch in diameter) become tan in the center and have a yellow halo (Fig. 2). Lesions can be numerous and spread from the lower leaves to upper leaves. In severe cases, lesions may grow together and can cause defoliation and/or yield reduction. Eyespot is also favored by cool, wet, and frequently rainy conditions. No-till and continuous corn production systems can also increase the risk for eyespot, as the pathogen is borne on corn residue on the soil surface. Management should focus on the use of resistant hybrids and residue management. In-season management is available in the form of fungicides. Again, fungicides should be applied early in the epidemic and may not be cost effective for this disease alone.

Anthracnose leaf blight (ALB): ALB symptoms include oval or elongated lesions that are brown in color and surrounded by a yellow or orange area (Fig. 3). Sometimes on older lesions, small black hair-like structures (setae) can be observed erupting from the leaf surface in the center of the lesions. In severe cases, ALB can result in leaf death that can affect yield. Again, the ALB pathogen overwinters on corn residue. Therefore fields in no-till and/or continuous corn production might be at higher risk for ALB. Long periods of rainy overcast and warm weather can favor ALB. Fields with poor soil fertility can also be at higher risk for ALB development. Management should focus on selecting resistant hybrids and residue management. Some fungicides are labeled for management of ALB, but control and yield increase in response to applications have been inconsistent.

Over the last several years there has been a lot of interest in applying foliar fungicides on corn to protect or increase yield. There are many products on the market and we tested several of these at various timings in 2013 on hybrid grain corn. The results of that trial can be found by clicking here and scrolling to page 2. In this study we had very low levels of common rust. Yield was highly variable in the trial and only one product/timing resulted in a yield increase over the non-treated plots. This high level of variability and inconsistency in treatment has also been observed in trials conducted throughout the corn belt of the U.S. over the last several years.

In a recent summary of foliar fungicide trials on corn from 2010-2013, 985 site/trials were conducted. No single product was identified to be more effective than another in these trials, however disease ratings were not the focus. When timing of fungicide application was analyzed, the best time to apply a fungicide and expect some yield increase over the non-treated control was between the VT and R2 growth stages. The average yield increase across all trials and years at the VT to R2 timing was 3.5 bushels per acre.

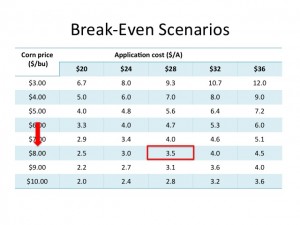

While there seems to be an overall positive response in yield with the application of fungicide, that increase is likely not high enough to recover the cost of application. A quick review of fungicide prices and expected application costs reveals that to apply fungicide one time might cost around $28 USD. Figure 4 shows a table of various costs to apply fungicide along the top, corn prices along the left column, and the bushel advantage required by the fungicide application to break-even with the cost of fungicide application in the center. The red box in figure 4 shows our 3.5-bushel average advantage that we saw across the region-wide trial. The arrow shows the corn price needed to recover the cost of one $28 fungicide application. This $8.00/bushel corn price is more than twice today’s average corn price!

The previous point on economics was made in the absence of disease on corn, however. When might we expect more consistent yield benefit from a fungicide? The answer is in the situations where disease levels are high of course! These situations include the following factors:

- Hybrids susceptible to foliar disease are used in fields with a history of disease

- Continuous corn production systems

- No-till or reduced tillage systems

- Late-planted corn

- Where irrigation is used

- Weather conditions are favorable for disease development

If one or more of these factors are important in your field, then scouting during the tasseling period will be important. Gauge the present levels of disease and look at the weather forecast to see if the epidemic might increase. Then make a consideration on if a fungicide application is needed in your field. Consider the economics of that application and also the fact that repeated application of fungicide can also promote fungicide resistance in some of the pathogens you might be targeting. So spray responsibly.