The following blog post was written as a part of a graduate level class assignment at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Of course much more work needs to be done in this area, but there is some interesting “food for thought” and should be considered the next time you might want to spray a fungicide. ~Damon Smith, Professor and Extension Specialist

Kelly Debbink, master’s student, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Have you ever wondered if fungicides can negatively impact soil microbes? Since their job is to kill fungi, it seems logical that they may have this effect on the fungi in the soil, right? This thought process is exactly what led me into reading a few too many published studies related to the topic.

Background

Let me start with a bit of what we know about soil microbes (mainly fungi and bacteria). Some microbes form symbiotic relationships with plants, through which they can colonize the root system (rhizosphere), the above ground plant surfaces (phyllosphere), and even internal tissues (endosphere). These microbes can help plants access nutrients and water, fight off diseases caused by other pathogenic microbes, and deal with stressful environments. Many other types of microbes may not form direct relationships with plants, but still live in the soil and provide services, like breaking down nutrients.

To carry out many of these useful activities, microorganisms produce diverse groups of enzymes. They are proteins that work to facilitate different processes and are necessary in many services related to soil health, including decomposing organic matter, nutrient cycling, and degrading hazardous compounds. Enzyme amounts are sensitive to environmental factors like pH and soil organic matter as well as management practices like crop type, chemical use, and fertilizer use. Any alteration of the soil microbial community will lead to changes in enzyme production, so they are commonly used as a soil health indicator. Lower enzyme levels are generally tied to less fertile soil and less productive crops.

So, if microbes are responsible for all these services, could we be causing them harm and hindering some of these services when we apply fungicides?

In my search I was specifically hoping to find field research instead of lab research, so I could find information that was a closer proximation to real life conditions. I will admit that most studies I found on this topic were performed in the lab by removing soil from an agricultural region, dosing it with fungicides, and running soil health tests on it. I did find a few field studies in which treated and non-treated plots were compared in normal cropping systems. These studies were all a bit different in their approaches to measuring changes, and they tested many different fungicides with different modes of action, so I would not compare these studies side-by-side to each other, but I will share some general trends that appeared in their results.

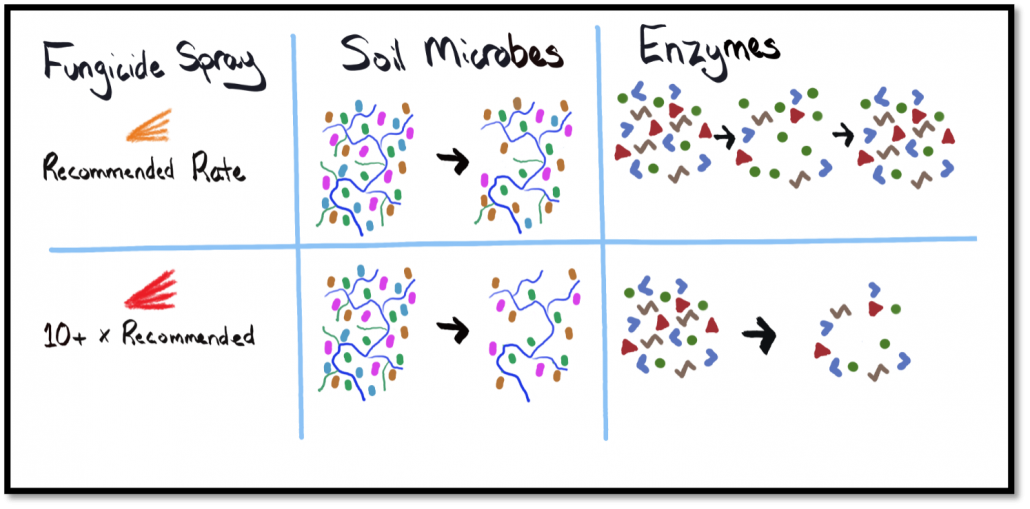

Soil Microbes

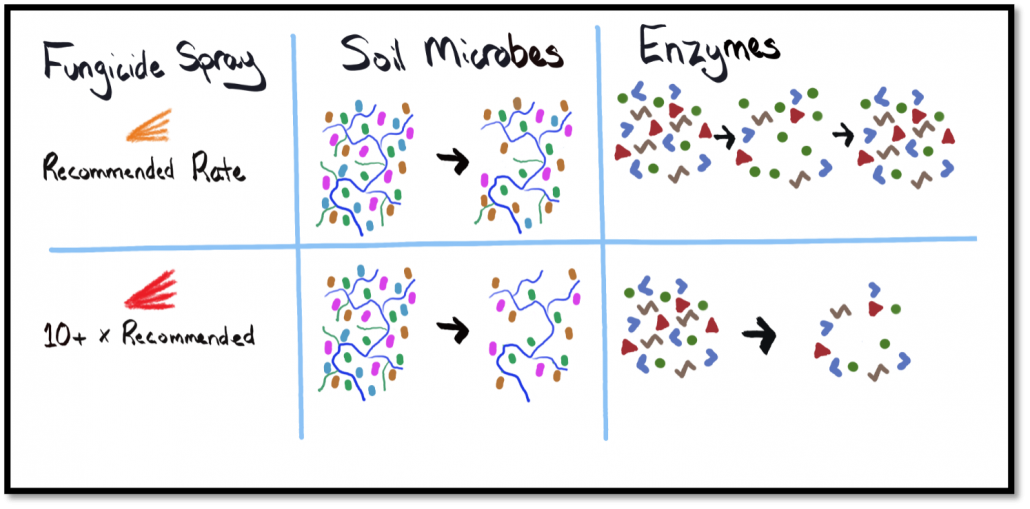

To start, there do appear to be shifts in some of the fungal and bacterial communities related to fungicide treatments. In a study that looked at seed coatings (fungicides & insecticides), these did not appear to decrease the richness (total # of microbe species) but did shift the abundance of different groups of microbes. In another study, the number of culturable bacteria and fungi were decreased, which at least suggested a decrease in richness of the subset of microbes that are culturable on lab media. Other lab experiments showed declines or shifts in the fungal community, but differing results on the bacterial community (they may decline as well or may increase). In some conditions, bacteria may be able to thrive once they have decreased competition from fungi. In one field trial, the label application rate and 2x the label rate led to short-term declines in measures of viable microbes. These declines all recovered by harvest. Additionally, this study tested 10x the label rate, but in this treatment, microbes remained low through harvest.

Soil Enzymes

Shifts in soil enzymes related to microbial activity and nutrient cycling were observed in multiple field trials. The general trend appears to be that at lower fungicide application levels, like label rate and twice the label rate, these enzymes may shift up and down, but often return near normal levels by harvest time. In contrast, the study that applied 10x the label rate observed declines in most enzymes that did not recover by harvest. This suggests that improper overuse or accumulation of fungicides may be detrimental to soil functions like nutrient cycling.

Conclusion

Overall, there are many environmental conditions that play a role in soil fungal and bacterial populations and enzyme activity. Many management decisions can have an impact on these, like crop rotation, tillage, and fertilizer use. Chemical use, like fungicides and other types of pesticides, likely also play a role in at least short-term shifts in soil microbes and enzyme activity. Obviously, the main goal of these fungicides is to control disease, and they are certainly a useful and necessary tool to protect crop yields and minimize disease. However, these studies do help remind us that there can be negative soil health effects to their overuse, in addition to the increased risk of pesticide resistance. It’s a good reminder that fungicides are only one tool in the toolbox, and other management decisions like choosing resistant varieties can help us control disease with fewer necessary fungicide applications.

References:

Background

Turner TR, James EK, Poole PS. The plant microbiome. Genome Biol. 2013 Jun 25;14(6):209. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-209. PMID: 23805896; PMCID: PMC3706808.

Chettri, D., Sharma, B., Verma, A. K., & Verma, A. K. (2021). Significance of Microbial Enzyme Activities in Agriculture. Microbiological Activity for Soil and Plant Health Management, 351–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2922-8_15

Field Trials

Hou, K., Lu, C., Shi, B., Xiao, Z., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Cheng, C., Ma, J., Du, Z., Li, B., & Zhu, L. (2022). Evaluation of agricultural soil health after applying pyraclostrobin in wheat/maize rotation field based on the response of soil microbes. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 340, 108186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2022.108186

Saha, A., Pipariya, A., & Bhaduri, D. (2016). Enzymatic activities and microbial biomass in peanut field soil as affected by the foliar application of tebuconazole. Environmental Earth Sciences, 75(7). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-5116-x

Nettles, R., Watkins, J., Ricks, K., Boyer, M., Licht, M., Atwood, L. W., Peoples, M., Smith, R. G., Mortensen, D. A., & Koide, R. T. (2016). Influence of pesticide seed treatments on rhizosphere fungal and bacterial communities and leaf fungal endophyte communities in maize and soybean. Applied Soil Ecology, 102, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.02.008

Lab Experiments

Han, L., Xu, M., Kong, X., Liu, X., Wang, Q., Chen, G., Xu, K., & Nie, J. (2022). Deciphering the diversity, composition, function, and network complexity of the soil microbial community after repeated exposure to a fungicide boscalid. Environmental Pollution, 312, 120060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120060

Cycoń, M., Piotrowska-Seget, Z., & Kozdrój, J. (2010). Responses of indigenous microorganisms to a fungicidal mixture of mancozeb and dimethomorph added to sandy soils. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 64(4), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2010.03.006