Damon L. Smith, Field Crops Extension Pathologist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Shawn P. Conley, Extension Soybean and Small Grains Agronomist, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Winter wheat planting is well under way in Wisconsin. While planting is the top priority, it is never too early to start making pest and disease management decisions for the 2014 wheat crop. In making wheat disease management decisions, consider the major disease issues in your area and develop your management plan according to the highest priorities. For information about some of the more common wheat diseases in Wisconsin, visit the Wheat Disease page of this website. There you will find diagnostic guides and also management information.

In addition to variety selection, a major component of disease management in wheat is fungicide use. It is important to consider the various fungicide options and carefully review efficacy information, such as Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Wheat Diseases, compiled for the north central region. For detailed information on fungicide efficacy, mode of action, mobility, and preventing fungicide resistance, read the Field Crops Pathology Fungicide Information page.

2013 Fungicide Trials

In 2013 we evaluated fungicides in two trials located at the Arlington Agricultural Research Station in Columbia county. Both trials were planted using the soft red winter wheat (SRWW) cultivar ‘Kaskaskia’. Fungicides were applied using a CO2 pressurized backpack sprayer equipped with TTJ60-11002 Turbo TwinJet flat fan nozzles calibrated to deliver 20 GPA.

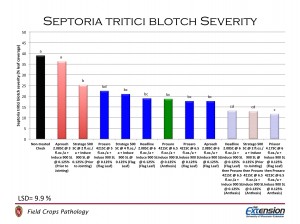

Figure 3. Septoria tritici leaf blotch severity. Black bar indicates the non-treated check; red bars indicate fungicide application prior to jointing; blue bars indicate fungicide application at emerging flag leaf; green bar indicates fungicide application at anthesis; broken bars indicate two-application programs. CLICK ON GRAPH TO VIEW A LARGER VERSION

In the first trial, fungicides effective on the most common diseases in the area (leaf blotch, powdery mildew and scab) were applied either just before jointing (Feekes 5), at emerging flag leaf (Feekes 8), at anthesis (Feekes 10.5.1), or using two sprays with the first occurring just prior to jointing or at emerging flag leaf and the second spray being applied at anthesis (Figure 3). Natural sources of pathogen inoculum were relied upon for leaf blotch and powdery mildew, and the plots were also inoculated with Fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of Fusarium head blight (scab).

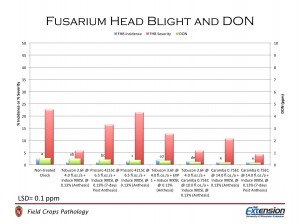

In the second trial, fungicides were applied in same manner as described above, but were targeted for scab control only and applied at anthesis (Feekes 10.5.1) or 7-days post anthesis only (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Fusarium head blight incidence and severity and DON levels in plots treated with fungicide. CLICK ON GRAPH TO VIEW A LARGER VERSION

Results

In the first trial the primary disease was Septoria tritici leaf blotch. Non-treated check plots had almost 40% leaf blotch severity.

Plots that received Priaxor 4.17SC at emerging flag leaf, followed by Prosaro 421SC at anthesis had the lowest levels of leaf blotch (Figure 3). Plots that received fungicide at emerging flag leaf (blue bars) or two applications of fungicide (blue and red dotted bars) had significantly less leaf blotch than plots that received fungicide prior to jointing. Most of these same treatments were not significantly different from the Priaxor 4.17SC/Prosaro 421SC treatment.

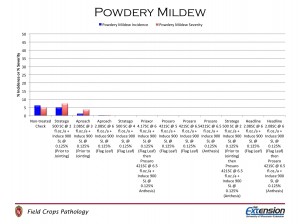

Figure 5. Powdery mildew incidence and severity in plots treated with fungicide. CLICK ON GRAPH TO VIEW A LARGER VERSION

Non-treated check plots had the highest levels of powdery mildew, however, severity was only about 5%. Therefore, there were no significant differences in powdery mildew incidence or severity among plots treated with fungicide (Figure 5).

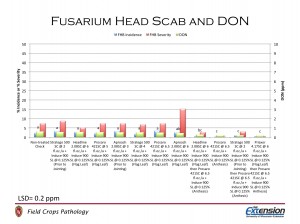

Figure 6. Fusarium head blight (scab) incidence and severity and DON levels in plots treated with fungicide. CLICK ON GRAPH TO VIEW A LARGER VERSION

Although plots were inoculated with the scab fungus, incidence and severity of scab remained low in the non-treated checks (Figure 6). No significant differences in the amount of scab were observed among plots treated with fungicide and the non-treated control.

There were significant differences in the levels of the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (DON). DON levels were not considered high (the FDA has established thresholds of 1 ppm in finished food products or 5 ppm in feed for animals such as pigs), but plots that received fungicide at anthesis had the lowest levels of DON.

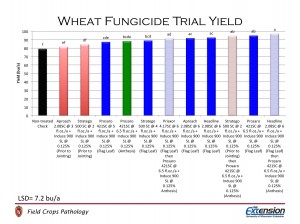

Grain yield in plots not treated with fungicide were near 80 bu/a (Figure 7). Fungicide sprays typically resulted in a significant increase in yield over not spraying, with the exception of applications of fungicide just prior to jointing. The highest yield was observed in plots that received Headline 2.08SC at emerging flag leaf , followed

Figure 7. Yield of wheat treated with fungicide. Black bar indicates the non-treated check; red bars indicate fungicide application prior to jointing; blue bars indicate fungicide application at emerging flag leaf; green bar indicates fungicide application at anthesis; broken bars indicate two-application programs.

by Prosaro 421SC at anthesis. All other two-spray treatments and flag leaf ONLY applications of Aproach 2.08SC, Headline 2.08SC, and Prosaro 421SC resulted in comparable yields to the highest yielding program.

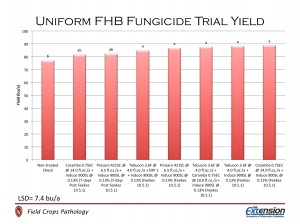

Figure 8. Yield of wheat plots treated with fungicide programs. CLICK ON GRAPH TO VIEW A LARGER VERSION

In the second trial incidence and severity of scab was again low enough that there were no significant differences among treatments (Figure 4).

While DON was not considered “over threshold” in the non-treated checks there were again significant differences in the levels of DON detected in plots treated with fungicide. Plots that were sprayed with Caramba 0.75EC or tank mixtures of this product had significantly lower DON levels than those that received Tebucon 3.6F, Tebucon 3.6F with an experimental fungicide (EXP1), or Prosaro 421SC. Only plots that received an application of Tebucon 3.6F at 4.0 fl.oz./a plus a non-ionic surfactant (Induce 900SL) had DON levels that were not different from the non-treated check.

Yield was significantly higher than the non-treated check in all plots that received fungicide at anthesis (Figure 8). Plots that received fungicide 7-days post anthesis yielded similarly to both the non-treated checks AND plots that received fungicide.

Summary based on these trials: Fungicide application on winter wheat in Wisconsin prior to jointing did not adequately control leaf blotch diseases. Application of fungicide at emerging flag leaf was the best application timing to control leaf blotch disease, which resulted in a significant improvement in yield.

Application of fungicide at anthesis may also be required in years when scab levels are high to control the disease and reduce DON levels in grain. Application of fungicide 7-days after anthesis was too late to reduce DON and improve yield over not treating with fungicide. As with all plant diseases, application of fungicide immediately prior to pathogen infection is the best time to treat.