Damon L. Smith, Extension Field Crops Pathologist, University of Wisconsin

The 2015 season has again been an interesting adventure. We managed to plant soybeans early or on-time in much of the state and then the rains started and have kept things fairly wet. Combined with cooler temperatures, this moisture has brought about the risk for several disease on soybean in Wisconsin. Of course the most notable disease is WHITE MOLD, but I already have written about this disease and discussed management strategies. If you would like to revisit this topic, CLICK HERE. You can also watch a short video on the subject HERE. Other diseases to watch out for during the mid-season include Septoria brown spot, brown stem rot (BSR), sudden death syndrome (SDS), stem canker and pod and stem blight, and soybean vein necrosis disease (SVND). I will consider each one of these diseases below.

Leaf spots caused by the fungus Septoria glycines. Photo credit: Brian Hudelson, UW Plant Disease Clinic

Septoria brown spot

Septoria brown spot is a common disease occurring on soybean each year. The spores of this fungus are typically rain splashed from old soybean debris, to the growing plants. Septoria brown spot is usually not considered a yield limiting disease, but in certain cases, it has been attributed to significant yield loss. This is usually the case where a susceptible variety is grown in a location conducive to the disease and rain is frequent and heavy. In a situation like this, fungicides might be required during the reproductive phase of growth to preserve yield. However, most of the time, Septoria brown spot is observed early in the season and again late in the season during periods of heavy rainfall and does not affect yield.

Symptoms include dark brown spots on both upper and lower leaf surfaces. Adjacent lesions frequently merge to form irregularly shaped blotches. Leaves become rusty brown. Symptoms of Septoria leaf spot can also develop on stems and pods of plants approaching maturity. Stem and pod lesions have indefinite margins, are dark in appearance and range in size from flecks to lesions several inches in length, but they are not distinct enough to be diagnostic. Seed are infected but symptoms are not conspicuous.

The onset of Septoria leaf spot symptoms is influenced by the relative maturity of the soybean variety, and symptoms appear earlier in the season on an early-maturing variety. Complete resistance has not been identified in soybean varieties or lines, but varieties do differ in partial or rate-reducing resistance which can be used effectively. Crop rotation is an effective preventative strategy. Septoria leaf spot is more severe in continuously cropped soybean fields. The host range includes most species of Glycine, other legume species, and common weeds such as velvetleaf. For fields with very high levels of Septoria leaf spot, plow under soybean straw to promote rapid decay. Application of fungicides to soybean foliage from bloom to pod fill has effectively reduced the severity of Septoria leaf spot in research trials over the last several seasons. However, yield has not been effected by these applications. Therefore, the odds of a positive return on investment when using a foliar fungicide on soybean to control Septoria brown spot are low. You can check out the results of foliar fungicide trials on soybean in Wisconsin by CLICKING HERE. You can also view the soybean fungicide efficacy table HERE.

Browning of the internal stem (left) is diagnostic for BSR. The middle stem may be developing symptoms. Compare to healthy, white pith in the stem on the right.

Brown Stem Rot (BSR)

Symptoms of BSR are usually not evident until late in the growing season and may be confused with signs of crop maturity or the effect of dry soils. The most characteristic symptom of BSR is the brown discoloration of the pith especially at and between nodes near the soil line. This symptom is best scouted for at full pod stage. Foliar symptoms, although not always present, typically occur after air temperatures have been at to below normal during growth stages R3-R4, and often first appear at stage R5, peaking at stage R7. Foliar symptoms include interveinal chlorosis and necrosis (i.e., yellowing and browning of tissue between leaf veins), followed by leaf wilting and curling. Yield loss as a result of BSR is generally greatest when foliar symptoms develop. The severity of BSR symptoms increases when soil moisture is near field capacity (i.e., when conditions are optimal for crop development).

Foliar symptoms of BSR can be confused with those of sudden death syndrome (see description below). However, in the case of sudden death syndrome (SDS), the pith of affected soybean plants will remain white or cream-colored. In addition, roots and lower stems of plants suffering from SDS (but not those suffering from BSR) often have light blue patches indicative of spore masses of the fungus that causes SDS.

BSR is caused by the soilborne fungus Phialophora gregata. There are two distinct types (or genotypes) of the fungus, denoted Type A and Type B. Type A is the more aggressive strain and causes more internal damage and plant defoliation than Type B. P. gregata Type A also is associated with higher yield loss. P. gregata survives in soybean residue, with survival time directly related to the length of time that it takes for soybean residue to decay. Thus, P. gregata survives longer when soybean residue is left on the soil surface (e.g., in no till settings) where the rate of residue decay is slow. P. gregata infects soybean roots early in the growing season. It then moves up into the stems, invading the vascular system (i.e., the water-conducting tissue) and interfering with the movement of water and nutrients.

Several factors can influence BSR severity. Research from the University of Wisconsin has shown that the incidence and severity of BSR is greatest in soils with low levels of phosphorus and potassium, and a soil pH below 6.3. In addition, P. gregata and soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) frequently occur in fields together, and there is evidence that BSR is more severe in the presence of this nematode.

BSR cannot be controlled once plants have been infected. Foliar fungicides and fungicide seed treatments have NO effect on the disease. Use crop rotations of two to three years away from soybean with a non-host crop (e.g., small grains, corn, or vegetable crops), as well as tillage methods that incorporate plant residue into the soil. Both of these techniques will help reduce pathogen populations by promoting decomposition of soybean residue. Also, make sure that soil fertility and pH are optimized for soybean production to avoid overly low phosphorus and potassium levels, as well as overly low soil pH. Finally, grow soybean varieties with resistance to BSR. Complete resistance to BSR is not available in commercial varieties. However several sources of partial resistance that provide moderate to excellent BSR control are available. Also, some, but not all, varieties of soybean cyst nematode (SCN) resistant soybeans also are resistant to BSR. Most soybean varieties with SCN resistance derived from PI 88788 express resistance to BSR. However, the same is not true of varieties with SCN resistance derived from Peking. Therefore growers should consult seed company representatives about BSR resistance when selecting a variety with SCN resistance derived from this source. You can download a full color fact sheet on BSR by clicking here. You can also CLICK HERE to view a short video on BSR.

Soybean Leaf with Symptoms of SDS

Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS)

The first noticeable symptoms of SDS are chlorotic (i.e., yellow) blotches that form between the veins of soybean leaflets. These blotches expand into large, irregular, chlorotic patches (also between the veins), and this chlorotic tissue later dies and turns brown. Soon thereafter entire leaflets will die and shrivel. In severe cases, leaflets will drop off leaving the petioles attached. Taproots and below-ground portions of the stems of plants suffering from SDS, when split open, will exhibit a slightly tan to light brown discoloration of the vascular (i.e., water- conducting) tissue. The pith will remain white or cream-colored. In plants with advanced foliar symptoms of SDS, small, light blue patches will form on taproots and stems below the soil line. These patches are spore masses of the fungus that causes the disease.

Foliar symptoms of SDS can be confused with those of brown stem rot (see description above). However, in the case of brown stem rot (BSR), the pith of affected soybean plants will be brown. In addition, roots and lower stems of plants suffering from BSR will not have light blue spore masses.

Once symptoms of SDS are evident, yield losses are inevitable. Yield losses can range from slight to 100%, depending on the soybean variety being grown, the plant growth stage at the time of infection and whether or not SCN is present in a field. If SDS occurs after reproductive stages R5 or R6, impact on yield is usually minimal. If SDS occurs at flowering however, yield losses can be substantial. When SCN is present, the combined damage from both diseases can be substantially more than the sum of the damage expected from the individual diseases.

SDS is caused by the soilborne fungus, Fusarium virguliforme (synonym: F. solani f. sp. glycines). F. virguliforme can overwinter freely in the soil, in crop residue, and in the cysts of SCN. The fungus infects soybean roots (by some reports as early as one week after crop emergence), and is generally restricted to roots as well as stems near the soil line. F. virguliforme does not invade leaves, flowers, pods or seeds, but does produce toxins in the roots that move to the leaves, causing SDS’s characteristic foliar symptoms.

SDS cannot be controlled once plants have been infected. Foliar fungicides have NO effect on the disease. Recently a new seed treatment has been identified that has efficacy against SDS. A multi-state university-based research team has demonstrated that ILevo seed treatment can reduce the effect of SDS and increase yields in fields where SDS is a problem. Other methods of control include using SDS-resistant varieties whenever possible in fields with a history of the disease; however, keep in mind that SDS-resistant varieties with maturity groups suitable for Wisconsin and other northern regions (groups I and II) are somewhat scarce at this time. If SDS and SCN are both problems in the same field, planting an SCN-resistant soybean variety may also be beneficial in managing SDS. Avoid planting too early. Wisconsin growers typically prefer to plant soybeans before May 10 to extend the length of the growing season and maximize yields. However, planting when soils are cool and wet makes plants more vulnerable to infection by F. virguliforme. Improve soil drainage by using tillage practices that reduce compaction problems. Rotation, while useful in managing other soybean diseases, does not appear to significantly reduce the severity of SDS. Even after several years of continuous production of corn, F. virguliforme populations typically are not reduced substantially. Research from Iowa State University has shown that corn (especially corn kernels) can harbor the SDS pathogen.

For more information CLICK HERE to download a full color fact sheet on SDS. A short video on SDS can also be viewed by CLICKING HERE.

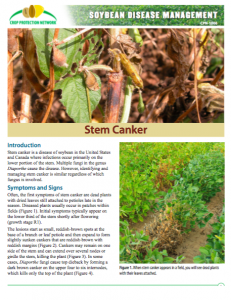

Patches of soybean plants killed by stem canker.

Stem Canker

There are actually two different types of stem canker caused by related, but different fungi. The fungus Diaporthe caulivora causes northern stem canker, while southern stem canker is caused by Diaporthe meridionalis. These two pathogens are part of the larger Diaporthe-Phomopsis complex, which consists of Phomopsis seed decay, pod and stem blight (see link to fact sheet below), and stem canker. In Wisconsin, northern stem canker is the most common stem canker disease, however, southern stem canker has been found.

Cool, wet conditions in the spring and early summer favor infection by the northern stem canker fungus. The symptoms of the disease become apparent later in the season. Considering the cool and rainy weather that has been prevalent over much of the state this season, it isn’t surprising that northern stem canker is prevalent.

Initially symptoms of northern stem canker appear as small reddish-brown lesions near nodes. As lesions expand, they can become more brown or gray, but the red border will remain. Eventually lesions of northern stem canker will get large enough to girdle the stems and may be confused with Phytophthora root and stem rot. The best way to tell these two diseases apart is to look for the location of the lesion. Generally with northern stem canker, lesions begin at nodes away from the soil line on the main stem and move upward. Phytophthora stem lesions will progress upward from the soil line. Northern stem canker can also occur in patches and damage plants in wide swaths Northern stem canker can also be confused with white mold when diagnosing above the canopy. Because the lesions can girdle stems, leaf flagging and death can resemble that of white mold damage. Therefore, careful scouting and inspection of the lower canopy and stems in necessary to tell the difference between white mold and northern stem canker.

Spores of the stem canker pathogen originate mostly from soybean debris from the previous crop. Therefore, severity of northern stem canker can be higher in fields with minimal tillage. Burying debris can help reduce the severity of the disease. Stem canker can also be more prevalent in fields with high fertility and high organic matter. Stem canker-resistant varieties are also available. Choose varieties with the highest resistance rating possible within the appropriate maturity group for your area. Soybeans rotated with alfalfa may also have a higher incidence of the disease, because alfalfa is an alternate host of Diaporthe. Fungicide application is not recommended for this disease.

You can download a new full color stem canker fact sheet by clicking here and for pod and stem blight by clicking here.

Symptoms of soybean vein necrosis disease (SVND)

Soybean Vein Necrosis Disease (SVND)

Soybean plants with SVND exhibit vein clearing (i.e., lightening of vein color) and chlorosis (i.e., yellowing), as well as mosaic patterns (i.e., blotchy light and dark areas) on affected leaves. Initially, symptoms develop around the veins of leaves and eventually expand outward. As the disease progresses, vein and leaf browning and necrosis (i.e., death) occur.

SVND is caused by soybean vein necrosis virus (SVNV). SVNV is in the viral genus Tospovirus. This group of viruses includes common vegetable viruses [e.g., Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) and Iris yellow spot virus (IYSV)] and ornamental viruses [e.g., Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV)] that can cause severe damage and substantial loss of yield and crop quality. Tospoviruses tend to have wide host ranges and are transmitted by several species of thrips. SVNV is also thought to be thrips-transmitted, but this has yet to be confirmed. SVNV may have been introduced to Wisconsin via thrips moving north on wind currents from the southern United States.

Currently very little is known about SVND. Thus there are no specific management practices recommended for SVND at this time. No specific control recommendations are in place. Researchers at universities across the country are attempting to determine what impact SVNV will have. Additional research is needed to determine how SVNV affects soybeans, how it is transmitted, how it overwinters, and what can be done to slow its spread.

To learn more about SVND you can download a fact sheet assembled by a multi-state working group of soybean pathologists and also view a short video.